I recall a cartoon reprinted in an intro psychology text many years ago. In it, two lab rats are returned to their cage from their sessions in “Skinner boxes.” This is a device that trains them to press a lever by reinforcing them with food pellets. One rat says to the other, “Boy, I really have this guy trained. Every time I press this lever, he drops this chunk of food in this trough.” While I don’t recall the point the cartoon was used to illustrate, I will provide my own: causality is often not a one-way street. Frequently it is a back-and-forth interaction.

Cause-and-Effect vs. Interactive Models of Behavior

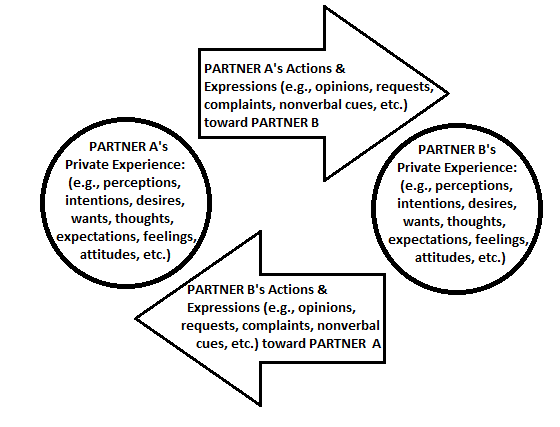

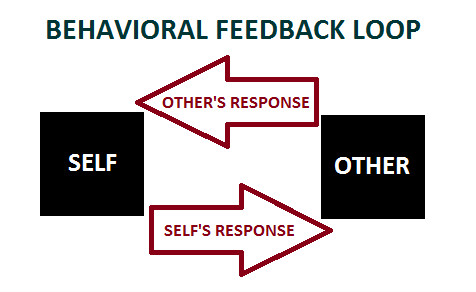

Most psychological approaches view individuals primarily in terms of how they interpret and respond to their environment. Behavioral psychologists focus on behaviors as conditioned responses to stimulus situations. Thus, they utilize a linear, cause-and-effect analysis. Often, they ignore how people alter their environments through their responses. Thus, an individual’s response affects others around them, which in turn presents the next situation to which they respond. This feature is taken into account in the feedback model below:

Public Behavior and Private Experience

Note that a strict behavioral model only studies publicly observable activities. This practice allows for external validation and consensual agreement, thus satisfying the requirements for verifiability demanded by objective science. Private experience, since it cannot be verified, is considered irrelevant. Thus, this approach considers the mind a “black box,” incapable of penetration through understanding, or offering no explanatory benefits. Thus, the strictly behavioral model avoid the pitfalls of unreliable self-reports of the persons being studied. It also avoids vague, ambiguous psychological concepts that cannot be directly observed. (For a historical background of these concerns, see my earlier posted article, A Brief Cultural History of Cognitive Behaviorism.)

While the above model meets the rigorous requirements for objective science, it has its limitations with regard to making changes, such as breaking out of the feedback loop, or vicious cycle. For instance, the model itself does not suggest which responses are more likely to break out of the pattern. Rather, in the language of science, that’s an “empirical question” or a “testable hypothesis” – which means finding the answer through trial and error. The question remains as to which hunches to check out first, with a strictly behavioral model offering little guidance.

AN INTERPERSONAL INTERACTION MODEL:

PLACING OUR EXPERIENCE AND BEHAVIOR IN A SOCIAL CONTEXT

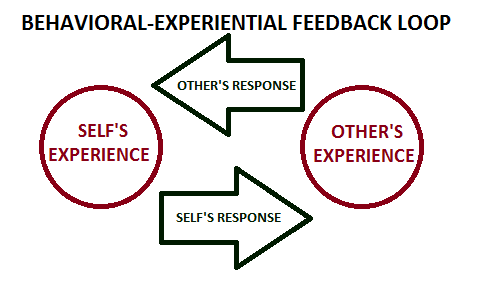

A modification to the feedback loop model can be helpful in proposing possible options for breaking the feedback loop, or vicious cycle. This change involves delving into the “black boxes” of the participants to understand how their personal experiences influence their behavior. This approach is based upon two assumptions: first, that individuals give meaning to behaviors, whether their own and those of others, by attributing various values, intentions, expectations, feelings, and motivations to them; and second, that this meaning plays a major role in determining the individual’s external, observable response to the situation. To address these concerns, we are adopting a behavioral-experiential feedback model, diagrammed below. Simply stated, this model recognizes that we interpret the actions of others as a step toward responding to them. For example, we infer the intentions of others from their actions, so that we are responding not only to their outward actions, but also to the perceived intentions behind those actions. Most people can appreciate this link between private experience and external expression, if they have enough of the right information – even if the objective behavioral scientists and social engineers either cannot or will not recognize the intuitive connection. Fortunately, most psychologists nowadays are attempting to penetrate those black boxes by asking their subjects about their own experiences and intentions and about the perceived intentions of others. In short, we recognize that people have an inner life, even if for some of us this has been a relatively recent rediscovery.

This model does not spell out the particular types of experience and behavior that are most relevant to the feedback loops. The choice is largely a function of one’s perspective, whether that be influenced by a particular psychological theory or by a more informal outlook on life. For example, a cognitive behaviorist would examine one’s cognitive belief systems that are associated with the observed behavior, whether one’s own or the other’s. A psychoanalytically-oriented therapist might focus on experiences outside the realm of conscious intention, (e.g., dreams) and behaviors beyond conscious control (e.g., “Freudian slips”) to discover unresolved conflicts that keep a person stuck.

An alternative to the theoretically driven approaches is a model in which the vicious cycle participants describe their own experiences and behaviors, as well as those of their partners. Of course, this introduces the very real possibility that the partners are fooled by the very assumptions, distortions, and “blind spots” that are driving the vicious cycle pattern. This is not an insurmountable problem, though. Not having access to one another’s private experiences, the partners can check out their assumptions about each others’ intentions and meanings behind the outward expression by asking them. In doing so, they may discover that what one perceived was not what the other meant, in which case they may be experiencing a misunderstanding, rather than a real conflict. (It makes little difference whether one did not express clearly what one meant, or the other heard something different that what was said. Of course, in many cases the conflicts are quite real, and thus require much more work that just clarifying misunderstandings. Later on in this article and in Living Rationally with Paradox and Muddling Down a Middle Path, both on this website, I address the issue of whether the conflict is a problem with a rational solution or a paradox that defies such logic. We will see that the latter case recommends attending to the feelings, wants, and needs of the partners. In doing so. we will recognize that there are real implications to viewing the conflict as a problem or a paradox, particularly in terms of the approach that is needed to resolve it.

BASIC FORMAT FOR DIAGRAMMING THE VICIOUS CYCLE PATTERN

Our format for the vicious cycle pattern involves diagramming the patterns as an alternating interplay between the inner experiences and outward actions of the participants. Since we do not have direct access to others’ experience, we can infer it from their expression – the actions, verbal statements and nonverbal expressions occurring between the experiences of the two partners. Of course, we have another option: we can ask our partners about their private experiences.

DEFINING CHARACTERISTICS OF VICIOUS CYCLE PATTERNS OF RELATIONSHIPS

So far, we have designed a model of exploring the interpersonal dynamics in terms of a feedback loop involving alternating patterns of inner experience and outward expression between people, but we have not addressed the defining characteristics of vicious cycle patterns, the principle subject of this model. We can define a vicious cycle as a relatively enduring pattern of interaction, one that persists despite a lack of resolution of significant conflict and chronic distress among the participants. Perhaps a more accurate term for this phenomenon is “adverse mutual attraction feedback loop,” but that is a bit wordy and sounds too technical, so I’ll stay with the term, “vicious cycle,” which is closer to personal experience. In either case, the condition probably qualifies for Albert Einstein’s definition of insanity: doing the same thing over and over again and expecting a different result. So, beyond defining what a vicious cycle is, we want to identify the “active ingredients” responsible for the persistence of a condition that seems to defy logic.

Basic Criteria for Vicious Cycle Patterns

• Conflict-based – it involves opposing forces

• Complementary roles of the participants

• Failure to resolve the conflict

• Persistence of the roles, despite lack of success toward achieving a desired outcome

• Frustration of all the parties involved

• Repetitive nature of the interaction

THE VORTEX PHENOMENON

Perhaps one way of understanding the workings of vicious cycle patterns is to apply an analogy from fluid dynamics. (Okay, so you’re not an expert in this field of physics, but you do know about hurricanes and tornadoes – in fact, you might even be fascinated by them.) Here we are talking about the turbulence that develops when two opposing forces collide, with a vortex developing when there is even a slight imbalance at the interface. So when warm, humid air collides with cooler, dry air, tornadoes, one type of nature’s vicious cycles, are prone to form. (Presumably, if the opposing forces were totally balance, there would be a stalemate or an impasse, rather than a vicious cycle.) With this being a positive feedback loop, the phenomenon tends to strengthen over time, although other factors may be introduced that either strengthen or weaken the effects. Other examples in nature include, dust devils, whirlpools, and maelstroms.

The use of a metaphor of a tornado or a hurricane can help us to appreciate the nature of vicious cycles on an intuitive level. I might pose the question of whether the relationship between hurricanes and vicious cycles in relationships is simply one of a metaphor and its referent, or whether it might be one of resonance, in which the very same process is at play in very different fields. As an aside, chaos theory addresses another process that has broad application across vastly different fields. This probably has little or any relevance to the practical matter at hand, yet it makes for interesting speculation about a certain unity in nature. But I digress.

CONFLICT: THE ENGINE FOR THE VICIOUS CYCLE

The introduction of the analogy of a vortex allows for us to examine the forces and energy that drive a vicious cycle. Our various needs, wants, desires, and feelings are the fuel providing the energy for the vicious cycles. It would be quite unusual for them to be in harmony with one another, or with the needs, wants, desires, and feelings of our partners, all the time. So, internal conflict is basic to the human condition, and interpersonal conflict is a normal, and even healthy, aspect of relationships, as I have addressed in Dealing with Conflict in Relationships: The Art of Assertiveness. Conflict is the state in which the various needs, wants, desires, and feelings oppose one another, whether interpersonally or internally. Conflict is the engine that drives the vicious cycles, fueled by disparate wants, needs, desires, aversions, and feelings.

THE PARADOXICAL NATURE OF MANY CONFLICTS

While conflict can often be viewed as a type of problem, it does not necessarily have a logical solution. Many conflicts reflect the inherent paradoxical nature of human experience, and perhaps of reality itself. And because of their paradoxical nature, these conflicts defy simple, logical solutions. (See Living Rationally with Paradox and Muddling Down a Middle Path for a detailed discussion of this point.) I bring this up now simply to note that the attempt to resolve a paradox though a rational solution may prolong and intensify the conflict, feeding into the vicious cycle pattern. This will be explored later, as we explore the Critic – Victim/Rebel vicious cycle.

VICIOUS CYCLE PATTERNS: AN ISSUE OF PROCESS, NOT SUBSTANCE

One important point to note about a vicious cycle pattern is that often the process of conflict (i.e., how we deal with it) poses a greater obstacle to its resolution than does the content or substance of the conflict (i.e., the real differences on issues). This idea is developed further in the post, When Is a Conflict Not a Real Conflict?.

EXAMPLES OF VICIOUS CYCLE PATTERNS

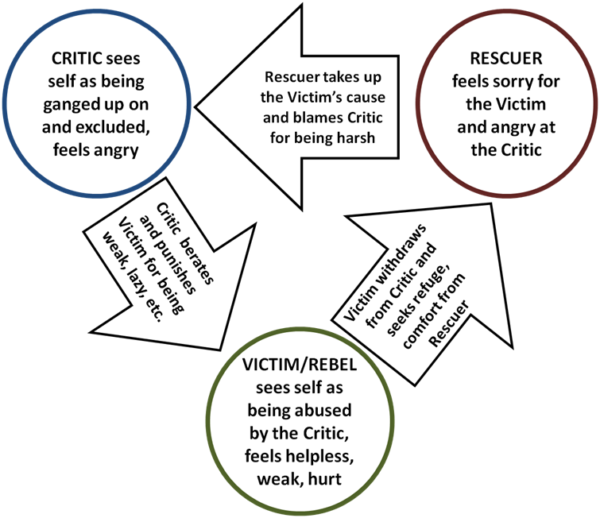

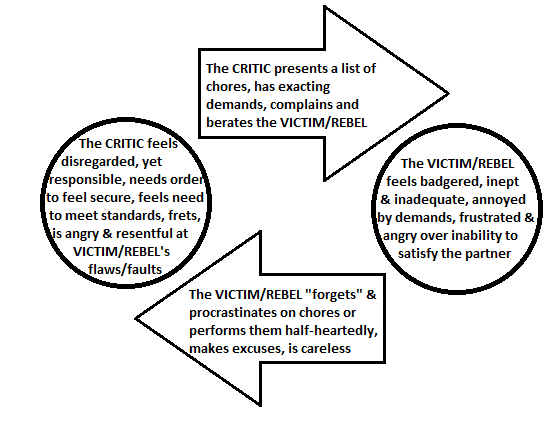

Thus far, we have been addressing vicious cycle patterns in the abstract, and we can use some examples to make them more real and experiential. Perhaps the prototype is the Persecutor – Victim – Rescuer cycle, otherwise known as the Drama Triangle, which was identified by Stephen Karpman and addressed in Games Alcoholics Play, by Claude Steiner (1971). Note that this is actually a three-party vicious cycle, whereas the models presented above are all two-party diagrams – still, the same principles apply. I have fit the patterns into my format, in which inner experience is in the circles and behavior, or external expression, is contained in the connecting arrows. I have also modified the titles somewhat. I view the Critic as a somewhat broader category than the Persecutor, yet one which is just as relevant to this cycle, so I am substituting the term. Also, I have come to the conclusion that the term Victim conveys a bit more passivity and helplessness than is often present in that role, so I have substituted the term Victim/Rebel to suggest a more defiant attitude, however passive and sneaky, to this role.

THE CRITIC – VICTIM/REBEL – RESCUER CYCLE

Adapted from the Persecutor—Victim—Rescuer cycle, by Stephen Karpman, in the book, GAMES ALCOHOLICS PLAY.

For the case study illustrating this dynamic, I have referred to the Beetle Bailey comic strip by Mort Walker, dated October 6, 1991. In this panel, General Halftrack’s wife (the Critic) scornfully predicts that he will stop off to have several drinks before returning home after golf. General Halftrack (the Victim/Rebel) becomes sullen and indignant at her insinuation of his lack of self-discipline. So how does he cope with his distress? That’s right – he finds solace at his favorite bar, where the bartender (the Rescuer) provides him with the alcohol to numb his pain. We can further assume that Mrs. Halftrack will continue to address her loneliness by nagging him even more for his drinking and absences. Though each spouse has a legitimate need – the wife’s wish for companionship and the husband’s desire for respect and confidence in him – each is responding in a manner that practically negates those possibilities. I would like to link to this particular comic strip, yet I have been unable to link to the internet archives, so you’ll have to settle for this narrative version.

There is another visual/narrative example I can refer to, which dramatizes this pattern within the family, in which the father assumes the Critic role while the mother assumes the Rescuer role in meting out punishment for the Victim/Rebel son. This takes place in For Better or For Worse, by Lynn Johnston, from January 1, 1993.

TWO-PARTY VICIOUS CYCLES DERIVED FROM THE DRAMA TRIANGLE

The following two patterns have been derived from Stephen Karpman’s Persecutor – Victim – Rescuer Cycle, otherwise known as the Drama Triangle, by taking two legs of the cycle at a time. These may not be quite as stable as the three-legged cycle, similar to a two-legged stool not being as stable as a three-legged one. As such, they may require some outside assistance from time to time to reinforce and maintain the pattern. For instance, one of the members may call in a family member or friend, perhaps in an attempt to escape the cycle, yet often with the result of maintaining the status quo, or equilibrium. A variation of this strategy is to call in a therapist to fix the problem. This presents some significant challenges for change, as addressed in the upcoming post, “The Therapist Role: ‘Pay No Attention to the Little Man Behind the Curtain.'”

THE CRITIC – VICTIM/REBEL CYCLE PATTERN

(AKA THE PERFECTIONIST – PASSIVE-AGGRESSIVE CYCLE)

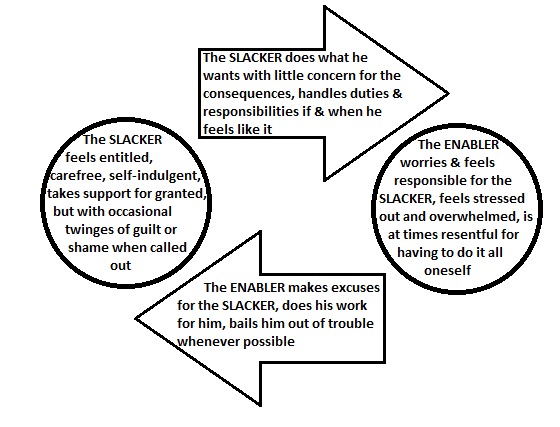

THE SLACKER – ENABLER CYCLE

(Note that this is similar to the Critic – Victim/Rebel cycle, except that the Slacker lacks the distress of the Victim, as the Enabler coddles whereas the Critic blames.)

CASE STUDIES ILLUSTRATING THESE PATTERNS

Now that I have diagrammed these patterns, some examples are in order. Rather than presenting case studies that illustrate the often tragic fallout from such patterns, I choose to dramatize these cycles from the public media. Scott Adams presents a beautiful example of the Slacker – Enabler pattern in the December 24, 2006 Dilbert comic strip. Besides demonstrating how the overfunctioning of someone with perfectionistic tendencies encourages the underfunctioning of the entitled slacker, the strip shows how the enabler can easily shift into the critic role. Another illustration with a similar message is the Baby Blues comic strip from October 14, 2005, by Rick Kirkman and Jerry Scott.

STABILITY IN SYMMETRIC AND ASYMMETRIC VICIOUS CYCLE PATTERNS

My diagram of the Critic—Victim/Rebel cycle (also known as the Perfectionist—Passive-aggressive cycle) is much the same as the “Protest Polka” presented by Dr. Sue Johnson in her book, Hold Me Tight. She identifies this as a “Demand—Withdrawal pattern,” in which “one partner becomes critical and aggressive and the other defensive or distant.” I would suggest that my format of diagramming the Experiential-Behavioral Feedback Loops can be helpful in illustrating this particular pattern, as well as the other two behavioral patterns that she describes in what she calls “Demon Dialogues.”

Whereas this particular pattern of demand and withdraw, whether labeled “Critic – Victim/Rebel” or the “Protest Polka,” involves asymmetric-yet-complementary roles (i.e., different, but reinforcing one another), Dr. Johnson’s other two defined patterns, that of the “Freeze and Free” and “Find the Bad Guy,” involve generally symmetric roles. While she identified the former as a Withdraw—Withdraw pattern, the latter can be characterized as an Attack—Attack cycle. Both of these are examples of positive feedback loops, which results in an escalation of the behaviors and leads toward instability in the relationship. Unchecked, mutual withdrawal over time leads to the weakening of the emotional bond between the partners and the eventual dissolution of the relationship. Unrestrained mutual attack can escalate the conflict to physical violence, which has been grimly dramatized in the movie, The War of the Roses. These two symmetrical patterns of disengagement pose an interesting question: which is the opposite of love – hatred or indifference? Other than the risk of physical injury and death, it may matter little whether the relationship dies of fire or of ice.

Dr. Johnson aptly notes that these patterns occur in all relationships, yet become habitual in the less secure ones. With the positive feedback loops of the two symmetrical patterns (i.e., withdraw—withdraw and attack—attack), some fluctuation in patterns is required to maintain a somewhat viable emotional space between the partners. Perhaps the couple is able to compartmentalize their differences and achieve a truce during the times that the conflict is inactive in their lives, until those differences again come to the surface. A less comfortable option is the hot-and-cold alternation between hostile engagement and withdrawal. Of course, the optimal resolution is to find more effective ways to work through the conflicts and to work at healing from the emotional pain endured by all the parties to the conflict. This latter approach takes work, and many partners in relationships prefer to continue with their familiar patterns rather than venturing into the unknown and threatening territory of emotional intimacy. Thus, they may be like “The Man with a Leaky Roof,” which presents an apt parable about doing damage control without fixing the problem.

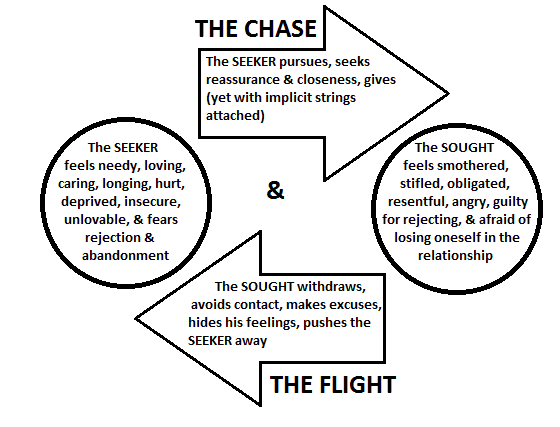

The complementary-yet-assymmetric patterns diagrammed in my article are negative feedback loops, which is a technical way of saying that they tend to foster homeostasis, or a stable state of affairs. In the case of personal interaction, we can talk about this in terms of emotional space, with the emotional distance determined by the dynamic interplay of the flight of one partner and the pursuit by the other. This has been dramatized extensively the book, The Two-Step: The Dance toward Intimacy (1985), written by Eileen McCann and illustrated by Douglas Shannon. The emotional space between the partners tends to stay within a certain range, and any deviation from that range can be easily corrected, either by pursuit of the Seeker to close the gap, or by the flight of the Sought to increase the distance. The pattern of this interaction is presented in the following diagram:

THE CHASE – FLIGHT CYCLE

(Adapted from The Two-Step: The Dance Toward Intimacy,

by Eileen McCann and Douglas Shannon)

The following two examples are derived from the book, The Two-Step: The Dance Toward Intimacy, by Eileen McCann and Douglas Shannon (1985). The book uses various cartoon illustrations to depict the dynamic struggle between partners who have much different comfort levels for interpersonal and emotional distance, with the Seeker preferring more closeness, while the Sought wants his/her space. The figure below summarizes many of these dynamics and embed them in the model of the behavioral-experiential feedback loop.

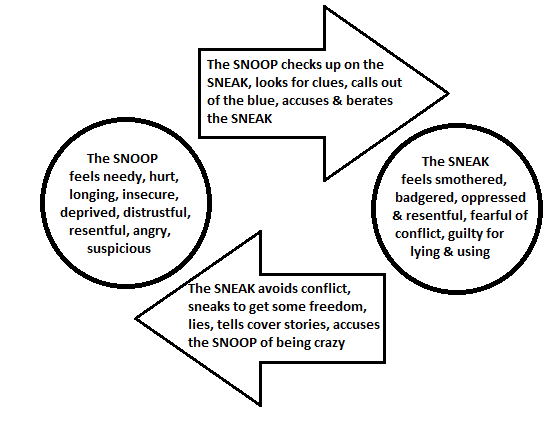

THE SNOOP AND SNEAK CYCLE

AN ESCALATION OF THE CHASE – FLIGHT CYCLE,

COMMON IN ALCOHOLIC – CODEPENDENT RELATIONSHIPS

The Snoop and Sneak Cycle represents an escalation of the Chase – Flight Cycle. This commonly occurs when there has been a significant breach in the relationship, due to some letdown or betrayal. This commonly occurs when the Sought partner seeks emotional relief in a manner unacceptable to the Seeker, and thus feels the need to hide his/her tracks. The outlets may involve sexual affairs, substance abuse, pornography, gambling, compulsive shopping, eating disorders, self-injurious behaviors, etc. We can consider these outlets as Enablers, in which case this resembles the Critic – Victim/Rebel – Rescuer cycle, though I prefer the label “Sneak, Snatch, and Snoop” cycle. Another variation of a third-party involvement is when another party catches the Sneaky one in the act and informs the Snoop, in which case we have a Snoop, Sneak, and Snitch cycle.

APPLYING THE VICIOUS CYCLE MODEL

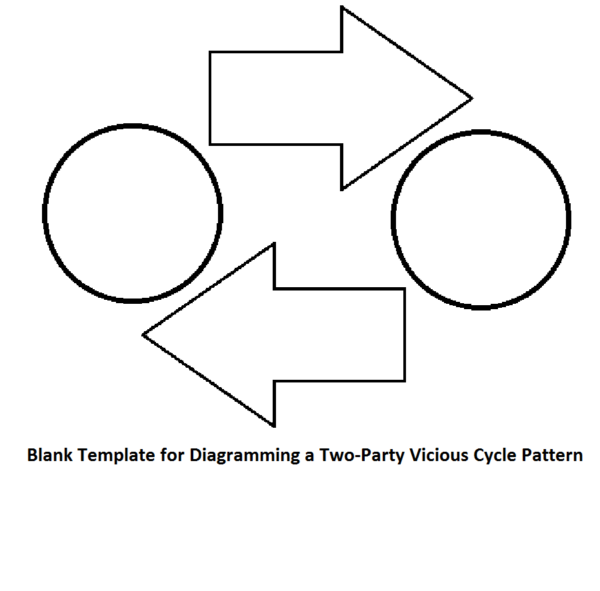

The above examples are some of the more common vicious cycle patterns. I continue to be amazed at how readily my clients relate to them when I share them – even the standard patterns “off the rack,” rather than custom-tailored. When they don’t exactly fit, certain alterations may be in order. Thus, a Blank Template is provided at the bottom to make the adjustments – or to construct an entirely new cycle. Of course, it is probably best to have the contents of the circles (i.e., inner experiences) and arrows (i.e., outer expression and behavior) filled in by the experts – the participants of the vicious cycles themselves! After all, only the individuals themselves have direct access to their inner experiences). Of course, it probably doesn’t hurt for them to have a copy of the Template with General Guidelines for Diagramming a Two-Party Vicious Cycle, shown earlier in the article, or perhaps a copy of the example that more closely resembles their particular situation, to use as a starting point.

While the cycles tend to be relatively persistent, they are not constant and continuous; rather, they tend to get activated under stress, particularly with conflict (just like a leaky roof, which only leaks when it’s raining). There can be some fluctuations in the patterns, as well. Note that the circles represent roles or character styles, and not the persons themselves. With that being the case, people have the freedom to alternate between roles. Of course, people tend to gravitate toward certain roles according to their personality types and approaches to life. Some people are rather set in their styles and thus may tend to stay “in character” with one particular role, while others are more flexible and may alternate between the various roles, depending upon the situation. One example is the Victim/Rebel role, whereby a son might adopt a passive-aggressive “sitdown strike” of the Rebel role in response to scolding and demands from his father in the Critic role, while shifting into the posture of a Victim when presented with the opportunity for sympathy and support from his mother in her assuming the Rescuer role. Another common example is for a usually compassionate spouse to shift from the Rescuer role to the Critic stance when she decides that her husband is acting like a deadbeat. These examples all point out a limitation to the Behavioral-Experiential Feedback Loops used to diagram the vicious cycle patterns: these are static structures used to describe dynamic processes. Though relatively persistent, the various vicious cycle patterns wax and wane over time and situation, and at time alternate with one another. Still, the diagrams can be useful in capturing the major trends, and two or more patterns can be identified on different templates when there is more than one dominant pattern.

BREAKING FREE OF THE CYCLE

Now that we have addressed how vicious cycles operate and identified some of the common patterns, we are ready to apply this knowledge and understanding to learn how we might break free from this distressing and limiting pattern of relating. We begin doing this by recognizing and identifying the particular pattern in which we find ourselves stuck. The real challenge with this is to include ourselves in the picture, as we are likely to have some “blind spots” in how we see ourselves. Just as we cannot view our whole body directly, but must depend on a mirror for some views, we may need others to reflect back to us some things that we may not be able or willing to see in ourselves. The Gospels of Matthew and Luke recount Jesus observing that we often fault others for the mote or splinter in their eyes, while not recognizing the beam in ours. This condition is also dramatized in the Luann comic strip of January 10, 2003, by Greg Evans, in which Luann’s friend, Delta, was rather unaware of her selfless qualities, even when Luann commented on them.

Once we have identified the patterns of experience and behavior that contribute to the vicious cycle, we can diagram the interaction patterns, using the Experiential – Behavioral Feedback Loop introduced earlier in this article. While not essential to understanding the pattern, the diagram allows us to visualize the process in action.

One of the essential ideas to remember about this process is the need to work at changing the one part of the process that we have some control over – namely, our own experience and behavior. Many people go astray in this area, instead focusing on how they might make over their partner. It is important for us to realize that trying to change our partners to suit our needs or expectations is disrespecting their autonomy. That does not mean that we can’t ask for what we want from them – not only is that simply being assertive, but it is likely to be more effective. Here I might state a paradox of change, namely that influence works best with others (and perhaps with ourselves) when we give up the illusion of control.

One change in perspective that applies to all vicious cycle patterns is the realization that everyone participating in the vicious cycles loses in one way or another – there are no real winners. For example, victims failed to develop their potential with regard to personal competence, caretakers lose themselves in becoming consumed in their efforts to rescue victims, and critics alienate victims and caretakers alike through their judgmental attitudes. When we realize that we all get swept up in the process and that we are not actually intending the negative outcome, we can have compassion for all parties involved. Here, I paraphrase a proverb from the Tao Te Ching, which states that those who understand how the system (i.e., vicious cycle) operates can have compassion for all the members participating in it. This realization can help us to let go of judging and blaming, whether directed toward others or toward ourselves.

Another helpful insight to keep in mind is that we do not have the corner on the truth, even if we are “being objective about it.” I cite my front page article, About “A Rogue Psychologist Field Guide to the Universe,” which makes the point that objectivity provides a perspective on reality, but is not reality itself. Or as Alfred Korzybski cautioned, “The map is not the territory.” When this realization sinks in, we are more likely to be receptive to other perspectives on situations, recognizing that others can have valid points of view without discrediting our own.

In working on changing our part in the vicious cycle, we can focus on our personal experience and our behavior and expression, (the contents of the circle and the arrow in the diagram, respectively). Here, there are some basic guidelines that we can follow, regardless of the particular role or roles we have adopted in the vicious cycle. First, we can strive for greater congruence between our own personal experience and our self-expression to others. In other words, we can strive for the WYSIWYG (what you see is what you get) ideal, that involving letting what is on the inside show on the outside. This approach is certainly not recommended for all circumstances, as it can be rather risky and even harmful to our self-interest s when taking this approach with strangers or business acquaintances. (A poem I wrote some years ago, A Poem in Honor of D. H. Lawrence, addresses how a certain opaqueness in our being can protect us from the demands by others.) On the other hand, transparency is particularly relevant for deepening our closeness in our special relationships.

Another point to keep in mind is to recognize that some changes that we might attempt are not sufficient to bring about “system changes,” with the system being the vicious cycle pattern. Here, we can recognize that “rearranging the deck chairs on the Titanic” would not have kept it from hitting the iceberg and sinking. Furthermore, some apparent changes are simply a variation on a theme, or “same song, second verse.” The saying “the more things change, the more they stay the same” also refers to such apparent changes.

UNDERSTANDING THE VICIOUS CYCLE ROLES

Now that we have explored how the process works, we can focus on the particular roles toward which we find ourselves gravitating. Remember that while we may take on certain roles in vicious cycle patterns, we are not those roles, even if we play them rather often or even habitually. Yet we do volunteer for certain roles because they fulfill particular values, wants and needs which we endorse. Many of these evolve out of our efforts to resolve the various paradoxes in life (e.g., order versus freedom, safety versus excitement, being versus becoming, belonging versus individuality, using versus relating), which have been spelled out in my Muddling down a Middle Path and Living Rationally with Paradox articles. It is rather unlikely that such resolutions represent a deliberate choice evolving out of our contemplating these paradoxes and the meaning of life. Rather, the resolution is typically implicit rather than directly stated – that is, implied by our actions as we engage with others. As such, these perspectives go unstated, making them quite difficult to challenge. Once we identify them, we are more likely to consider that there are other options available. Tagging these ways of being in the world with labels gives us the focus to assess their usefulness and to consider other options. I will be doing this tagging by identifying the implicit motto’s people live by, which often pull them into particular vicious cycle roles. My plan is to post separate articles that identify the working mottoes of some of the most common roles in vicious cycles. Two such articles are Escaping the Victim Role and Caretaker Burnout and Compassion Fatigue. (Hopefully, breaking the topic into smaller, more manageable pieces will aid in the digestive process.) I also plan to identify the most relevant paradoxes for each of the roles, as well as suggesting more effective resolutions to them.

A HELPFUL ATTITUDE OF THIS QUEST

This work can be rather daunting, so it is helpful to have a proper attitude. First, while you may well have a good idea where you want this work to take you, it is important to take on this challenge one battle at a time, rather than trying to win the war with an Extreme (Personality) Makeover. Recognize that practicing changes in behavior and perspective helps to create new habits of thoughts, feelings, and actions. Making changes of habits clustered in related areas can lead to developing positive traits, such as compassion, assertiveness, generosity, responsibility, spontaneity, organization, and self-reflection, many of which are related to paradoxical dualities. As addressed in my Muddling article, shifting toward a middle ground on the continuum of paradoxical dualities, such as between organization and spontaneity, typically leads to more adaptive styles of interaction. When we have progressed in resolving our paradoxes in several areas, we can achieve a transformation of who we are and how we relate to the world around us, thereby accomplishing the overall goals we have identified for ourselves. Yet it is also important not to get overly concerned about the outcome: after all, it’s the journey, not the destination. The Tao Te Ching reminds us that “a journey of a thousand miles begins with a single step,” to which we might add, “and then another step, and then another, and then the next, etc.” So with this being said, find some good traveling companions, and hang on and enjoy the trip.

This is a terrific website, easy to understand and follow. Glad I came across it.