Pilgrimages often reveal their most poignant insights during the journey, rather than at their destinations. The demanding physical ordeal of the trip itself poses a trial of perseverance. For cloistered monks, though, the quest offers additional challenges. The journey often exposes them to the temptations, distractions and aggravations from which the monasteries have shielded them. Unplanned and unanticipated events along the way test their commitment to their spiritual paths. In the process, the monks have the opportunity to renew and deepen their spirituality.

The Two Monks on a Pilgrimage

Such was the case with two monks who embarked upon this quest. Brother Kim was a novice, relatively new to the monastery. He looked upon Brother Lee as his mentor. In particular, he admired his elder’s equanimity in his deep spiritual practice within the sheltered confines of their monastery. Their pilgrimage was their first venture outside the monastery together, opening up opportunities for spiritual teaching. Little did they know just how this quest would test their fraternal bond.

The Course of the Pilgrimage

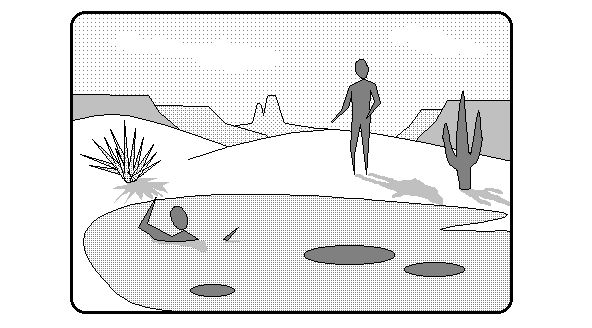

We withhold the pilgrimage’s route and destination so as to protect its sanctity for this order of monks. Recognize, though, that it is a strenuous journey, crossing two ridges and two valleys before arriving at the sacred grotto. As it turns out, each descent and river crossing embodied a particular trial. The preceding day’s torrential rains made the trails muddy and slippery. The rivers in the valleys had become swollen, making ferry crossings impossible and ford crossings treacherous. Still, with diligence and caution, our two monks could wade across. Others, particularly those of slight or frail build, found the crossings impossible – but we get ahead of ourselves here.

The First Crossing

After descending into the first valley, our two monks catch sight of the swift-flowing stream. There, on the riverbank, they catch sight of a fair young maiden, one of radiant beauty. She – the proverbial damsel in distress – sought their help in crossing the river. She explained that the swift current blocked her access to her ailing father across the valley. Without even thinking, Brother Lee lifted her up in his arms and proceeded to carry her across at the river ford. He noted to himself how her additional weight, however slight, lent greater stability to his footing. He felt his feet pressing into the muddy bottom, grounding him and helping him to resist the current.

Meanwhile, Brother Kim was quite unsettled by her beauty, leading him to avert his gaze from her. He was ever so aware of his vow of chastity, and he fought hard to honor it. Eventually, he managed to regain sufficient composure to allow him to navigate the swirling waters to the far bank. There, the maiden and the two monks parted ways, she into the valley, and they up the path to the next ridge.

The First Reckoning

The monks proceeded on their journey, climbing the next ridge and following it a ways. Brother Lee was rather nimble and light on his feet, while Brother Kim was downright klutzy. The young novice was constantly tripping over twigs, brushing against tree limbs, and getting snagged in vines. Soon, his aggravation was readily apparent to his mentor. Brother Lee inquired, “What’s wrong? Why are you so out of sorts? You weren’t like this at the start of our trip.”

After a deep sigh, the novice spewed forth, “How could you? We are supposed to be on a sacred quest, and you grab that beautiful girl and lift her to your bosom – I mean, chest.– Then caress her in your arms as you sway about in the churning torrent. What happened to your repudiation of the flesh, and your vow of purity? Does that mean nothing to you? And to think that I looked up to you and sought your guidance!”

When Brother Kim’s rant subsided, a tense silence followed. Then, Brother Lee casually noted, “My young brother, I left that young maiden back at the riverbank. You’ve been carrying her with you ever since.” Gradually, the silent pall lifted, and they continued on their way.

The Second Crossing

Before long, our two monks descended into the next valley. There, they soon approached its river, just as swollen as the previous one. As they neared the bank, a shriveled, contorted figure slumped before them. Here was likely the vilest, most ill-tempered curmudgeon that either of them had ever encountered. And that was before the wretch had even opened his mouth! His screechy voice conveyed utter contempt as he demanded immediate passage to the other side.

Whereas most would be taken aback by this demeanor, Brother Lee acted without hesitation. He heaved the wretch over his shoulder and proceeded into the swift stream. The monk immediately noticed that the riverbed consisted of slippery, loose rocks, requiring constant adjustments to stay upright. These maneuvers provoked the wretch’s barrage of complaints, curses, and insults, liberally punctuated by jabs and slaps. In his passage across the river, Brother Lee maintained an acute focus on maintaining his balance. He came to a startling realization – all these adjustments were actually helping to center him in his body! He even felt a hint of exhilaration, as a bronco-busting cowboy might experience.

Meanwhile, Brother Kim grew increasingly impatient with the abusive wretch. This frustration was no doubt built on the foundation of his earlier disappointment with his mentor. (Although he had come to understand and appreciate his mentor’s stance, his body still retained a substantial residual tension.) And while he was rather indignant on behalf of Brother Lee, he was also quite disappointed in him for tolerating that abuse.

The Second Reckoning

Upon reaching the far shore, the monks parted ways with the ill-tempered curmudgeon. They could hear his nagging complaints faded off into the distance as they headed down the trail to the grotto. The monks still had more ground to cover to reach the grotto by nightfall, so they hurried down their path. And as before, the mentor was fleet of foot and poised, while the novice was klutzy. This time, Brother Lee cut to the chase, “What’s the matter now, Brother Kim? You seem all out of sorts.”

After a deep sigh, Brother Kim let out a yelp. He then exclaimed, “This pilgrimage is not going at all as planned. I came looking for a deeper spirituality, and this is what we get – nagging complaints from that ingrate. He has totally ruined any possibility of spiritual transcendence that I was hoping to find. And as for you, how can you have any respect for yourself? You allowed that pathetic idiot to abuse you – both physically and verbally. Now, I’ve lost all respect for you.”

After a lengthy pause, Brother Lee responded, “My young brother, I left that poor wretch back at the riverbank, but you are still carrying that load with you. What a burden that must be for you, especially since you seem resigned to keeping it the entire journey.” After a while, he continued, “You know, you have a point about my tolerating abuse from that poor soul. I had not experienced such condemnation, I guess, since earlier today, when you denounced me for helping that young maiden. Now, that abusive wretch is no longer here with us, so it makes no sense to fret over him. But you are here with me. So how would you have me respond to your harsh judgment of me, both now and earlier in the day?”

The novice was stunned and speechless, and had no answer. Brother Lee allowed him his space, and the two completed their pilgrimage to the grotto in silence.

The Descent into the Grotto

Upon arrival, the two monks descended deep into the dark recesses of the grotto to complete their pilgrimage. There, they entered an extended silent retreat. Brother Lee, grounded and centered in his body from the stream crossings, sat in utter stillness with a quiet mind. Brother Kim, on the other hand, had some sorting out to do.

Danger: Proceed with Caution

The above parable, like The Monks’ Interesting, Not-So-Silent Retreat, is an adaptation and embellishment of a spiritual story in the Buddhist tradition. Minor variations of the original can be found by googling “fable monks taking maiden across the river” or similar phrases, so I assume that this story is in the public domain. You will also see that “The Second Crossing” in my story adds one or two new dimensions to the tale. Spelling them out is somewhat akin to explaining the punchline of a joke. Just as such an endeavor can spoil the humor, explanations can disrupt the story’s impact. So, if you share this concern, I advise you to skip the following commentary.

If you have resisted the urge to indulge in the following objective interpretation, I want to hear from you. How were you able to accomplish that? (Or are you just delaying it?)

Commentary on the Original Tale

The original tale follows the Buddhist tradition in dramatizing the spiritual path as a river crossing. It addresses the pitfall of fantasizing in desire for this pursuit, whether of deeper spirituality or simply serene mindfulness. This message is obviously relevant for monks and nuns with their vows of chastity and purity. Yet it is also relevant for those of us who have not disavowed our sensuality. Here, the challenge is to keep the sensuality embedded in a personal relationship, rather than expressed in unadulterated lust. This presents a more daunting challenge than faced by the monks. A secondary theme is the importance of honoring the vow’s spirit, not just the “letter of the law.” When we focus too much on the latter, we miss the forest for all the trees.

Commentary on my Embellished Version

This embellished version’s addition of a second river crossing expands upon how judgmentalism disrupts spirituality, or mindfulness. Such a constraint is implied in the “letter of the law” approach, as dramatized in the original version. My amended version notes how we can be intolerant of others’ shortcomings. Brother Kim was paradoxically hypercritical of the curmudgeon’s harsh treatment of Brother Lee. He also revealed his criticalness toward Brother Lee, both for presumed carnality and for tolerating abuse. Brother Lee modeled living in the moment by focusing on Brother Kim’s judgmentalism, as the curmudgeon was long gone. He further highlighted the challenge posed in responding to abuse, while modeling equanimity in the face of it.

I also snuck in a secondary theme, as well. This addresses the paradox that deeper spirituality often involves greater “embodiment.” Note how Brother Lee’s focus on his body experiences (both groundedness and balance), helped him maintain his poise. Thus, he could resist the distracting influences of sensuality, annoyance, and criticalness in his spiritual crossing.

If you decided to entertain the more objective perspective in this commentary, I welcome your feedback, as well.