Have you ever gazed up at the clouds and found human, animal, or mythological images, whether full-bodied or just facial, in them? If so, chances are that you have a condition known as pareidolia. For further assessment, though, take a look at the following figures:

What does this look like to you?

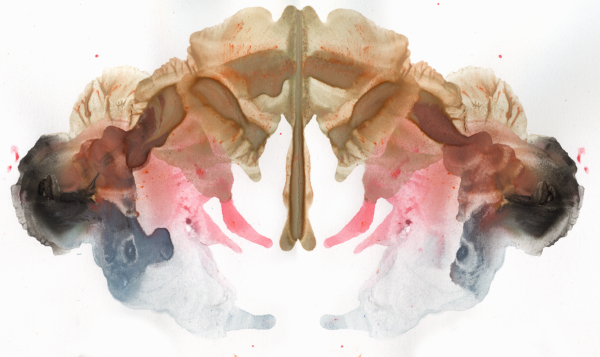

And this? What do you see here?

How about this? Does this look like anything to you?

What sort of images do you see in these splotches of ink? Animal, vegetable, or mineral? Or perhaps human, mythological, or extra-terrestial? Or maybe landscapes or seascapes?

Then again, you may only see them as blotches of ink – symmetrical, yes, but without any particular patterns or images embedded in them. If so, then you probably don’t have pareidolia, which is the tendency to see meaningful objects, human, animate, or otherwise, in ambiguous or random visual stimuli.

If you did see objects or meaningful images, you don’t need to be alarmed. Pareidolia is a normal condition that affects most people. It mainly causes problems when we have trouble distinguishing what is real from what is illusion. There are times when this condition can cause serious problems. These include visual hallucinations and drug-induced visions, such as a bad LSD trip. Here, the issue is more a matter of impaired reality testing than of the illusory experiences themselves.

In fact, pareidolia can be adaptive and beneficial. In the event of crises, recognizing danger in a split second can be the difference between life and death. Misperceiving an object as threatening is usually less risky than failure to recognize a real menace. Better to be safe than sorry! Pareidolia offers an advantage in evolutionary terms. Activating the fight-or-flight response quickly allows one to live and procreate another day.

Pareidolia and Psychological Projective Assessment

You may be aware that psychologists have used the pareidolia response as a projective technique for personality assessment. Interpretations are based on the variations in what people read into the ambiguous stimuli. Psychologists and psychiatrists having found that differences in these responses on the test instruments reflect more general differences in daily experiences and behavior.

Use of Pareidolia in the Clinical Case Study

Clinicians initially developed their use of pareidolia as a projective technique informally, through clinical case studies. They used their own particular theoretical perspectives to analyze their patients’ response patterns to the ambiguous stimuli, which they extrapolated to explain the psychological processes in daily life. They used their clinical intuition to integrate the considerable detail offered by the case studies, yet the theory determined what data was considered relevant, such that such an exploration and interpretation could hardly be considered objective and unbiased.

Use of Pareidolia in the Experimental Research Design

Subsequent experimental researchers questioned the scientific rigor of the case study approach, which they considered anecdotal. In effect, they were accusing the traditional clinicians of a process similar to the pareidolic activity of their subjects (i.e., reading meaning into subjective and ambiguous data without having objective verification). The experimental researchers such as John Exner undertook the challenge of testing the various hypotheses which the clinicians had proposed, but not proven objectively. This endeavor resulted in validation for some hypotheses but not for others. The findings were often in rather general terms, in contrast to the clinicians’ more specific interpretations derived from their intuitive analysis of the case studies.

Objective Personality Assessment

Regardless of whether the diagnostic approach involved clinical case studies or more rigorous experimental designs, the psychological interpretations used rather technical and abstract concepts to describe psychological functioning. This approach, with its appeal to objective science for its legitimacy, has a rather sterile, reductionistic flavor, particularly when contrasted with a more literary or humanistic approach to portraying life’s existential challenges. (Perhaps this is a major reason why psychiatrists and psychologists are often referred to as “shrinks.”)

Inkblots as a Trigger for Pareidolia

The Rorschach inkblots, a series of ten cards, is the most familiar of the various projective techniques. As with the other assessment instruments, researchers have conducted extensive research on how the pareidolic responses to the inkblots are related to more general styles of personality, and can thereby serve as indicators of these styles. Thus, these inkblots serve the objective analysis of human experience and behavior.

An Alternative Approach to Inkblot Interpretation

The inkblots shared in this post are not from the Rorschach set. Nor have there been any studies to establish the frequency of the various pareidolic responses to each of these figures. Thus, they have no current value as an objective technique to analyze the psychological processes of persons responding to these designs.

The absence of this scientific framework leaves an opening for an alternative approach – namely, a subjective exploration of the personal experience of encountering these ambiguous stimuli. Granted, it does not offer the certitude of pronouncements based on scientific objectivity. Yet I would suggest that this limitation is overshadowed by the depth of rich, subjective experience that it offers.

Rediscovering the Subjectivity of Experience

Rather than “shrinking” personal experience through objective analysis, this exercise can be mind-expanding in its appreciation of the ambiguities of the human condition. This is a topic which I explored in my article, Muddling Down a Middle Path: Wading through the Messiness of Life. By sharing our own personal responses to these inkblots, without the choke of objective analysis constricting our experience or censoring our sharing, we offer one another and ourselves windows into our psyches. And if that is too lofty of an aspiration for this exercise, well, we might just have some fun with it, as play feeds off of ambiguity.

But don’t take my word for it – try it, and see what happens. And don’t stop with your images – consider your thoughts, feelings, attitudes, and associations to the images. And if you dare, share your experiences with your friends, and see where it leads.

Here are a couple more inkblots to pareidolate. (I’m not sure that’s a real word – I’ve been known to neologize.) I’d be glad to hear back from you on your experiences.