By BOB DANIEL, Ph.D.

Every now and then we are blessed with some unique experience which may profoundly influence our lives. The events seem to fold together as neatly as any story ever told, yet they come out of our day-to-day reality. There is a dreamlike quality to them, though they occur at full wakefulness. These occurrences happen in a state of grace in which reality is saturated with enchantment. Just how frequently they occur is hard to say – perhaps they are happening all about us, though usually without our notice. And sometimes they descend upon us before we are ready, and only later do we discover the lessons contained within these experiences. Such is the case with my encounter with an Eskimo artisan who lost his art and soul, whom I met during my training phase in clinical psychology. I never could pronounce his native name, but it translates into English as “One Who Releases Spirits from Rocks.” Besides, he asked me not to share his Eskimo name, expressing a belief roughly comparable to those of indigenous groups who refuse to have their photographs taken, for fear of being robbed of their spirit. He actually anglicized his name himself, and permitted me to refer to him by it, “Hugh Livingstone.”

As I look back now the whole sequence has a surreal quality, such that I sometimes question whether the encounter actually took place at all. Then I wonder if it might have all been a dream, one which at best only distilled my more mundane training experiences and cloaked them in the dramatic excesses of fantasy. I reveal these occasional doubts with some apprehension, a concern that others who pride themselves in their firm objective grounding will readily dismiss this tale as merely the product of an overactive imagination. And yet one of the lessons that I learned years after that encounter is the futility of such skepticism concerning the actuality of events, as long as the remembrance has a ring of truth to it. And I must confess that even I was rather skeptical of this Eskimo’s tale, though he consistently assured me that his story was totally true. When I brought up the issue that the events seemed to violate the physical constraints of reality, he refused to argue – all he’d say was, “Don’t confuse Fact with Truth.” So with this caution, I will dispense with my idle philosophical musings and commence with the story, to the best of my recollection.

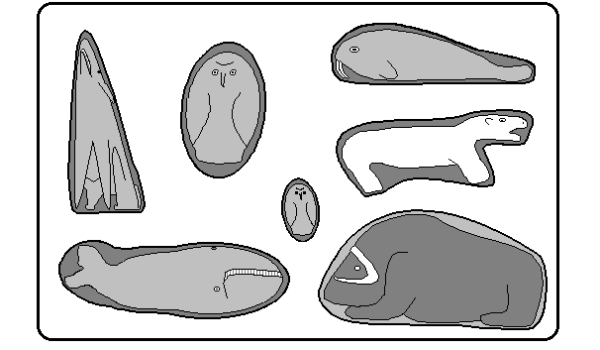

Hugh Livingstone was a sort of hermit who devoted most of his fifty-some years to the ancient craft of stone sculpture, which had been passed down for many generations in his family. The people of his village all revered the fantastic figures that he carved from what appeared to be rather ordinary stones. His process was always the same: he would take his time examining the stone, focusing very intensely on it, yet keeping his mind open and receptive, until the image that was locked inside the stone revealed itself to him. Then he would take his hammer and chisel, which he claimed were magical but which in fact appeared quite ordinary, to hew a few precise cuts into the stone, and the animal form emerged from the rock. A whole array of walruses, seals, polar bears, whales, yaks, marmots, eagles, ravens, and caribou came forth from the stones. Some of the forms were quite exotic to the Alaska tundra – tigers, boars, pythons, gazelles, kangaroos, and jackrabbits. The villagers were amazed by the extraordinary figures – they sometimes wondered how these strange stones found their way to Alaska from such faraway shores.

Hugh’s life was in harmony with his world, as were the lives of the other villagers – in harmony, that is, until the past few years, when the “ghost people” invaded the region to extract the natural resources from the land. The invaders from the lower 48 states found the name “ghost people” rather quaint, assuming that it referred simply to their lighter complexion. The villagers, however, based their perception of ghostliness not so much on skin color as on the unworldly mannerisms of the visitors: blank facial expressions, mechanical gestures and movements, and restricted vocal inflections. The villagers also noted that their landscape now appeared rather bleached out and deadened. Though disturbed by these changes, the villagers offered limited resistance, for they were comforted by the material prosperity and security which the invaders provided in exchange for the resources which they took from the land. The invasion apparently had a dramatic impact on Hugh’s art: many of his figures now were terrible and monstrous – dragons, gargoyles, dinosaurs, and gremlins – yet they all possessed the eerie beauty that marked his craft.

The invaders generally had little to do with the Eskimo culture: rather, they brought their own culture with them through VCR’s and satellite dishes, as well as the newly established taverns and chapels. Hugh’s craft offered the primary exception to this trend: many visitors found his figurines rather stylish or amusing, and they offered considerable money to possess them. A few of the ghost people actually became enchanted with the sculptures, some even noting that his stone figures were so life-like that they actually appeared to breathe. Hugh was initially perplexed by their response: their amusement and desire for possession were quite different from the awe and reverence his villagers bestowed upon his work. He was not used to the adulation doted upon him by the invaders, and he was quite taken in by it. His reputation quickly spread, such that scores of tourists went way out of their way to admire and buy his works. Others bought his pieces from a mail-order operation without even having seen them. He attained a celebrity status in his region of Alaska and became very proud of his fame and accomplishments.

Eventually Hugh was invited to present his works at a very prestigious art show in the lower forty-eight, without even having to apply for entry. The organizers even paid his expenses to attend. He was quite excited about making the long trip south, for he had never left his native village any farther than what his two feet could carry him in a week’s time. When the departure time approached and Hugh was busily packing, he discovered that he had few pieces remaining – he had sold practically all of his sculptures to the acquisitive tourists. It was too late to back out of the show, for he had committed himself to his village and his patrons, and he certainly did not want to disappoint them.

For the three remaining days and nights he worked constantly to produce an adequate stock for the art show. He no longer took the great care to discover the unique forms locked inside the stones. He had his customers to please and his own image to uphold, and that was foremost on his mind. So instead he took some of the standard forms that seemed the favorites of his customers, and he shaped the rocks into them. His attempts were by and large dismal failures. Most of the rocks turned out grotesque and malformed, yet lacking in the eerie elegance of his earlier monsters. Many of the stones fractured or crumbled under the impatient blows of his tools. Though he came up with a sufficient quantity of figures, they were quite disappointing to his fans and patrons, and a target of mockery for the art critics. Few bought his works, and in his shame he became as still and lifeless as the stones that he carved.

His stupor was so intense that his patrons could not even get him on the plane back North to his home. For weeks he refused to move or talk, sitting perfectly still. Having no other obvious recourse, his patrons had him admitted to the nearby state hospital, where he was diagnosed as having Catatonic Schizophrenia, Rigid Type. In the customary order of the hospital, I was assigned to work with Hugh. (Being at the bottom of the pecking order, trainees are routinely assigned the least promising cases, with the usually unexpressed attitude that there is less chance of doing harm.) I was content with this state of affairs, for a mute patient offers fewer opportunities to mess up, and I was just getting my feet wet with some real work. After a couple of weeks of regular daily sessions Hugh began to talk, yet all the while maintaining his rigid posture. He disclosed that he had become possessed by a terrible monster that could destroy anything or anyone in its path, and that the only defense against it was to lock it up inside a rock – hence, the catatonic rigidity. He revealed that the powerful medication put the monster to sleep, so that he could now talk in a whisper, so as not to awaken it. Hugh was quite taken with my interest, curiosity and patience, such that he referred to me as his shaman.

While I felt that Hugh was putting an inordinate amount of trust and confidence in me (and thus exercising poor judgment and reality testing), this did not stop me from proudly exhibiting my success in grand rounds. This move proved to be my undoing, for I emerged from my anonymity and received all sorts of encouragement and guidance as to how I should proceed with this now workable patient. In particular, I was encouraged to use the cognitive behavioral approach I was studying in my graduate training to challenge the patently irrational to outright delusional beliefs that Hugh was espousing. I must confess that at this point I was charged with enthusiasm, for now I would be doing real therapy, rather than merely supportive therapy, which I experienced as little more than faking it. Hugh’s trust and confidence were soon dispelled, however, when I began challenging his belief in the sleeping monster as no more than an irrational delusion. At that point he became highly volatile and explosive, destroying the furniture in the room and yelling out, “Sham, sham, sham.” After this outburst subsided, Hugh explained that I had awakened the monster, who then went on his rampage. If anything, my intervention had merely validated his delusion. These events had not escaped the notice of the ward staff, the training program, or my colleagues, and I received considerable attention, ranging from criticism and ridicule to condescension and sympathy. (I’m not sure which hurt worse.) Just as I had risen with pride, so had I plunged into despair. At the time I took little consolation from Hugh’s empathy, with his observation of the parallel between his own humiliation at the art show and my shame over his response to my intervention. (I’m not sure whether the role reversal or the accuracy of his comment troubled me more.)

Well, as for Hugh, the authorities at the state hospital did not appreciate his abdication of personal responsibility for his destructive actions, and they resented providing treatment to a nonresident who was so uncooperative with the program. They quickly arranged for his transfer back to Alaska. Not much is known about Hugh from this point on, for he returned to his village rather than being transferred to another state hospital. He did send me back a brief note, indicating that he was being treated by the shaman in the region. The monster had not been exorcised, but it had been tamed, such that Hugh viewed him as a faithful companion and protector. He was again sculpting stones, including some rather large boulders, but he was adamantly refusing to sell any of the pieces, for he now viewed that as a violation of his sacred pact: it was unfair to release the animals from the stones if he were only going to sell them back into captivity. I was pleased that he was again productive, though disappointed that he was not producing income and that he continued to be delusional.

Years later I have a fuller appreciation of my encounter with Hugh Livingstone. I address the lessons I have learned with some reluctance, for fear of reducing the experiences to a cold, abstract moral. Those readers who share this concern are invited to stop here, and others are advised to proceed at the risk of diminishing any air of enchantment derived from the tale. Though I still do not take all of Hugh’s pronouncements at face value, I generally view them as possessing a certain truth – even the “delusional” beliefs he espouses concerning his demon and the spirits he releases from rocks. This outlook can certainly be viewed as an argument against ethnocentrism and for multicultural relativism, thus endorsing the politically correct values of academia. Yet my realization concerns neither politics nor philosophy nor sociology, but personal reality (or phenomenology, to use the technical term). We could argue that his demon was simply his own rage over humiliation which he had refused to acknowledge as his own, and which therefore appeared alien to him. Or we could make a point that the spirits that were released through his sculpture came not out of the rocks, but from his own fertile imagination, and only resonated with the largely dormant spirituality of the so-called “ghost people.” Yet whatever such a translation gains in rational logic, it loses in access to a rich and unique perspective on the world. I see little to be gained from translating such poetry into prose, or from a related debate over literal versus metaphorical truth. I suppose these issues have their place, but not here, not now.

The primary lesson that I have learned is quite personal in nature, concerning an internal struggle for integrity, one that pits the ego against the broader self. I might paraphrase the message as, “Don’t sell your soul to boost your ego.” I grant that Goethe dramatized this lesson much earlier, but it was Hugh Livingstone, not Faust, who started me on the very personal quest of discovering the spirit hidden within mundane daily experience, both for myself and for the people I work with.

Bob Daniel, Ph.D. is a retired clinical psychologist who has been practicing in Virginia Beach for over thirty years. There, he worked in private practice with adults with mental health and substance abuse issues. Dr. Daniel has long valued stories and myths as vehicles of personal transformation, as noted in his post, Coping with Reality Through Enchantment: The Healing Power of Myth. He has been accused of being an unabashed prevaricator, but he insists that his stories are 100% true, even if not factually accurate. Another of his “true tales” is The Man with a Monkey on his Back, which addresses being our own worst critics. Still other tall tales, such as The Man Who Lost His Key and The Monks’ Interesting, Not-So-Silent Retreat, he borrowed and embellished from older folk and spiritual traditions. Dr. Daniel further explores our ability to infuse reality with our imagination in Are You Afflicted with Pareidola? .

You know Bob I really enjoy your stories about your former clients in therapy. The monkey story, Uncle Lester and the Eskimo are written quite well and you explain the situations in such detail I feel like I’m right there with you. I think you are at your best in therapy and writing about your personal experiences. It’s quite clear you are highly intelligent, but your writings on the technicalities of western psychology, paradoxes and cognitive behavior seem to get lost in terminology and deep rooted philosophical thought. I learned more about you and your way of thinking from your perspective in these 3 stories than any other articles you have written. Keep up the good work. I will be reading.

Thanks for your feedback. This encourages me to polish up some of the stories that are not entirely mine, but which have been around for many years and which I have adapted and embellished. Fortunately, I don’t have to choose between my analogies and my conceptual writings, as I can do both. I just have to decide which to do first. In processing our experiences, we use both modes of understanding to understand our world, and each has its place. To paraphrase a saying which I am currently unable to locate (but which may come from Indries Shah), “If you want to change a person’s mind, you give a lecture or a discourse; to touch a person’s heart, you tell a story.” I plan for some of my upcoming submissions to address the complementary nature of these two modes of understanding, the objective and the subjective. (By the way, my dissertation addressing the integration of these modes in the development of healthy selfhood.) I encourage further feedback, so that I can be more responsive to my readers.