How often do you stop to reflect on your place in the world and the social roles you play out on this stage? If you are like most, it’s not that often. You may follow the adage, “If it ain’t broke, don’t fix it.” This approach is in direct contrast to the Socratic dictum that “the unexamined life is not worth living” and his admonition to “know thyself.” Here, we find an example of contradictory advice, which I propose is a direct result of our living in a paradoxical world. As we discover in other writings on this site, we don’t need to be paralyzed by such situations. Instead, we can adopt a middle ground between the two opposing positions, in exploring not only how these social roles limit us, but also considering other available options.

Getting to Know Thyself

In exploring our usual styles of relating to others, it is important to remember that we are not the roles that we assume, even if we play them rather frequently or habitually. We may find that we alternate between various roles according to the circumstances in which we find ourselves. Still, we do “volunteer” for certain roles because they fulfill our particular wants and needs. Many of these roles evolve out of how we resolve various paradoxes of life for ourselves (e.g., order vs. freedom, belonging vs. individuality, security vs. excitement, being vs. becoming, and using vs. relating). It is quite unlikely that we have come to a deliberate choice out of our contemplating these paradoxes and the meaning of life. Rather, the resolution is usually implied in how we interact with others. And even if these roles were a product of conscious choice, we have likely practiced them sufficiently that they have become a matter of habit, with our no longer being aware of them. They then operate as implicit assumptions, acting behind the scenes to guide our interactions with others. As long as these assumptions go unstated, they are quite difficult to challenge. Only when we identify them, do we consider that there are other options. Tagging these “ways of being in the world” with labels gives us the focus to assess their usefulness and to consider other available options.

Social Roles – How to Define Them?

There is nothing magical or absolute about the labels and definitions for these social roles. It is more a matter of creating them, rather than discovering them. Just as we can cut a cake into different numbers of pieces of different shapes and sizes, so too can we construct the various roles from the array of attitudes, feelings, and behaviors that we experience and express. Even with this arbitrary quality, these labels provide useful “handles” for understanding ourselves. You will find that various therapists, counselors, life coaches, and self-anointed gurus differ widely in labeling and defining the common personality styles and roles. This is not haphazard. Rather, these categories are outgrowths of their perspectives on life. So, too, is it with my outlook. In particular, I make note of the differing styles we adopt and practice in wading through the “messiness” of living in a paradoxical universe. Furthermore, these roles do not occur in isolation – rather, they get expressed in our social relations. These habitual roles interact with others’ styles, often resulting in getting stuck in frustrating relationship patterns, which I have addressed as vicious cycles. Having labels and descriptions for these can help one escape from such ruts. While these labels can be a quite useful shorthand to describe common patterns, we should keep in mind that they are not things in and of themselves. Here, we want to keep in mind Alfred Korzybski’s adage, “Don’t confuse the map with the territory.”

Social Roles as Styles of Dealing with Life’s Paradoxes

In this approach, we will be defining our social roles in functional terms, according to the particular purpose toward which we are applying them. First, we define these roles according to varying tendencies for resolving life’s paradoxes: Do we seek out order and predictability, or do we reserve the freedom of keeping our options open? Do we prefer comfort and security, or do we pursue adventure and excitement? Do we live in the moment, appreciating things as they are, or do we focus on pursuing goals for improvement and fulfilling a purpose? Do we approach life and relationships in a practical sense of working together to achieve specific goals, or do we focus on relating to one another on a deeper emotional level? Do we collaborate openly with others by “laying one’s cards face up on the table,” or do we pursue our private agenda in “keeping our cards close to our vest”? Do we seek out a sense of belonging with others, or do we pursue our unique identity, “marching to the beat of a different drummer”? All of these questions tap into the paradoxes of life, for which there are no “one-size-fits-all” answers. Of course, these dualities are not forced choices between two extremes, but are two ends of a continuum, with the more adaptive approaches lying somewhere in the middle, as I discussed in my article, Muddling down a Middle Path: Wading through the Messiness of Life.

Getting Stuck in Vicious Cycle Roles

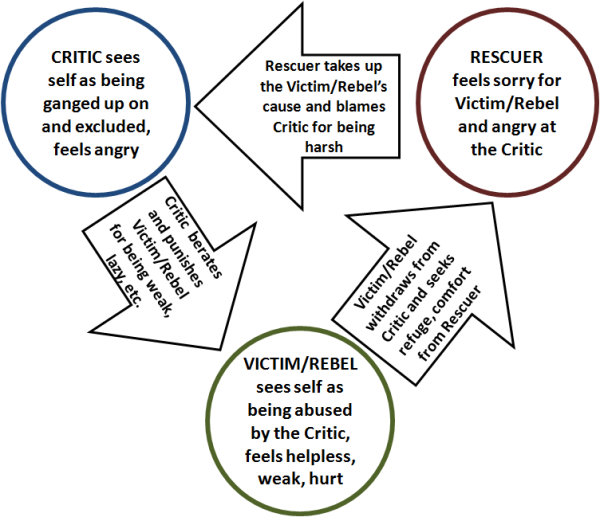

These paradoxes that shape our lives are no mere matter of philosophical debate. They get played out on the social stage on a daily basis. We find others to play out the scenes with roles that complement our own – though often not in a good way. Over time, these patterns become habitual, with little thought given to them, and even less consideration to what we can do differently. Thus, we get stuck in ruts which often bring out the worst in us, as I have discussed in my article, Vicious Cycle Patterns in Relationships 2.0.

Other posts involve exploring specific roles that have evolved out of my study of styles of resolving paradoxes and how these styles interact in vicious cycle patterns. Two such posts, Escaping the Victim Role and Caretaker Burnout and Compassion Fatigue, discuss specific unhealthy roles in vicious cycles and provide suggestions for breaking free from them. Future posts are in the works for transcending the Oppressor and the Rebel roles. Note that the goal of such projects is not to eliminate these roles, but to modify them to healthier versions. By offering adaptive solutions to problems and conflicts, the constructive versions allow us to venture beyond the vicious cycles and move on to other activities and social roles. The strategies and techniques specific to each social role supplement the more general tips given for escaping vicious cycle patterns, which were outlined in the Vicious Cycle article noted above.

Clusters of Related Social Roles

As I noted before, there is nothing absolute about these patterns, and thus we might look at clusters of patterns that function in much the same manner in vicious cycles. One such grouping, which I label the Oppressor cluster, encompasses the Critic, Perfectionist, Snoop, Bully, and Authoritarian roles. These represent variations on the Persecutor role identified by Steven Karpman, cited in the book, Games Alcoholics Play, by Claude Steiner. Another grouping, which I refer to as the Victim cluster, encompasses the Victim, Dependent, People Pleaser, and Martyr roles, which are versions of the Victim role in Karpman’s model. I also have identified the Rebel cluster as a variant of the Victim cluster, which encompasses the Individualist, Libertarian, Free Spirit, and Sneak social roles. I have adopted the Rescuer role in Karpman’s model as the foundation of another cluster, which also includes the Caretaker and Enabler roles. These clusters tend to complement one another in two-role and three-role vicious cycles, with Karpman’s Persecutor – Victim – Rescuer model serving as the prototype. (For a cultural and political application of this model, see my article, Vicious Cycle Roles on the Societal and Political Level.)