Social support is often crucial for bearing our stress, yet baring our souls is necessary for that to happen. Unless we open up, others cannot hear our pain and provide the needed comforting, encouragement, and understanding. This post explores how the Serenity Prayer offers guidance for choosing among these three listening approaches:

A Personal Approach to Pain and Stress

Few people relish the idea of embracing emotional pain. If we can avoid dealing with it, we often do. With repeated avoidance, our residual feelings – anger, sadness, resentment, shame, etc. – accumulate over time. As the various feelings get lumped together, they lose their definition. We forget the events that evoked them, as well as their meaning for us. Thus, we experience tension or discomfort, yet without a readily identifiable source or an obvious remedy.

Defining our Terms

Often, we have difficulty describing, or even naming, this vague condition. Here, we can borrow from health science the general term, “stress.” We can further specify “emotional stress” as the accumulated feelings which were not sufficiently processed and resolved. (I have at times referred to this as my trash compactor model of stress.) Additionally, we can define “stressors” as the particular events that triggered the feelings that make up the emotional stress.

General Stress Reduction

We have various outlets to relieve stress, in the areas of exercise, recreation, and relaxation. These approaches, though, are quite general. They do not address the specific stressors and feelings that contributed to the overall stress. And just where does that relief get you, if you continue accumulating stress? When similar situations occur (and they will!), these events will only evoke more distressing feelings. This may lead to a “revolving door,” where we encounter the same challenges, day after day.

A More Targeted Approach

Thus, we need to supplement our stress reduction efforts with a focus on the stressors behind the stress. This would involve recognizing the various feelings contributing to the accumulated stress. Then, we can identify the stressors triggering those feelings. At this point, the Serenity Prayer can help us sort out what we can change and what we must accept. Thus, an effective long-term approach to stress would include sorting out the various emotional components of the accumulated stress, identifying the stressors that trigger each of them, and working toward resolving them one at a time.

Developing Stress Tolerance

An approach to stress that addresses the various stressors at their source recommends not only strategies to reduce tension, but also methods for enhancing our stress tolerance. While tension-reduction techniques are certainly helpful for coping with stress, the active exploration of the stressors requires a willingness and a capacity to tolerate the related emotional pain. This is particularly true when we encounter complicated situations which require time to resolve: we must be able to bear the tension to see this process through.

Stress in Modern Times

Our modern society complicates this process further: our greater range of options carries a price of increased complexity and ambiguity. (This feature is explored in greater detail in my post, Muddling down a Middle Path: Wading through the Messiness of Life.) Interpersonal conflict complicates the matter further, as our differing values lead us to view various situations and issues differently. This complicates our task of negotiating, collaborating, and compromising to achieve mutually agreeable solutions. Thus, in a society such as ours that values individuality as well as community, we experience a greater pressure on our ability to tolerate stress.

On the Origins of Stress Tolerance

How do we increase our ability to endure emotional pain? To answer this question, it is helpful to consider how we developed this capacity in the first place. While some aspects are no doubt innate, we initially depended upon the tending and comforting of our caretakers to ease our distress. Without the ability to fend for ourselves, we required our parents to read our distress signals and to tend to our needs. Later, they helped us to label our various need states (e.g., hunger, thirst, fatigue, etc.), so that we could ask for what we want and need. While they tended to our needs and protected us from the objects of our fears, their calming and comforting presence soothed not only physical pain and discomfort, but also emotional distress.

As we grew older, our parents, teachers, coaches and mentors aided our independence by teaching us how to take care of our own needs, rather than our depending so much on others to meet them. They guided us in our efforts and encouraged us to take risks according to our abilities, building our confidence and countering our fears, distress, and anxiety. As we matured, we internalized these functions of comforting, understanding, and guidance, so that we could provide these functions for ourselves when our caretakers were unavailable.

The Legacy of “Dysfunctional Families”

Unfortunately, not all the concern from our caretakers helped us to tolerate stress. This is particularly true if we came from so-called “dysfunctional families.” In fact, the attention may have cultivated stress intolerance. For example, our caretakers may have been uncomfortable dealing with the pain, regardless of their actual verbal response. In this case, their obvious distress may have amplified our pain. Or our helpers may have avoided acknowledging the suffering by reassuring us that “everything will be all right.” If so, we may have felt all the more alone, feeling that no one really understood us. Or they may have admonished us to be strong, not weak. This may have encouraged us to suppress our pain, sending it underground, to be dealt with alone.

Coping with the Unavailable Caretaker

This resolution runs the risk that the pain later gets acted out in anger towards others, rather than being discussed with others or processed internally before being expressed appropriately. The rage reaction is all the more likely if our caretakers reacted with anger, either to their own frustrations or to ours. Unfortunately, we tend to learn these bad habits as well as the good ones. Such experiences leave us mistrustful and reluctant to express ourselves to others later in life, making the needed emotional support all the more unlikely. Not only does this limit our external support, it also thwarts our internalizing the functions of comforting, understanding, and encouragement, which are needed to develop our own capacity to bear pain and tolerate stress.

Letting Ourselves Receive Support

Even if our caretakers didn’t foster our capacity to endure pain, it’s never too late to work on it. As in our youth, this process works best with the caring support of others. Granted, the act of “pulling ourselves up by our bootstraps” may appeal to our pride. Still, this approach likely fosters a stoic manner, with its often undeveloped spontaneity, vitality, and compassion. It may indeed be rather humbling to depend upon others for emotional support when we figure we ought to be able to handle the situations for ourselves. On the other hand, such humility may grant us better appreciation of our common humanity through sharing our pain and suffering with one another.

Besides, such self-reliance may not be all that independent. It might just represent compliance with earlier messages from critical parents (e.g., “Be a man.”). The irony is that such pride in independence may have its roots in unquestioning conformity to parental authority.

Getting the Support We Need

Just how can others help us with bearing our pain? What makes their attention effective at comforting our distress? Here, there is no single answer, yet the Serenity Prayer can help us to understand the various components of a supportive approach. The prayer asks for “the serenity to accept the things [we] cannot change, the courage to change those things [we] can, and the wisdom to know the difference.” For each of these three personal qualities there is a complementary role of the listener who witnesses our pain: for serenity, soothing and comforting; for courage, guidance and encouragement; and for wisdom, understanding.

The Soothing Role in Attaining Serenity

Serenity, the first of these functions, involves a soothing and comforting that allows us to tolerate our pain. In contrast, distress or worry about the pain that we face amplifies our experience of the pain. Often, it is not the pain itself that is unbearable. Rather, it is our distress over dealing with or avoiding the pain that feels intolerable. A sense of dread or apprehension about the outcome of the painful episode is one possible aspect of this distress. Another is the sense that the events that evoked the feelings are unjust, violating some implicit rules we live by. Yet another is a sense of shame for our involvement in the events surrounding the pain. Here, we assume much of the blame and guilt for the happenings. This low self-worth may lead us to isolate ourselves from others whom we assume will judge us harshly.

Developing Acceptance

Here the supportive presence of others can do much to ease our distress and low self-worth. Their acceptance of us despite our shortcomings can bolster our self-worth that has been challenged by our stressors. They can give us a sense of their continuing support and caring regardless of how the surrounding events unfold. Our supporters can help us accept the current circumstances as a challenge to grow, despite the unfairness of the situation. Or they can guide us toward coping with what is, rather than complaining helplessly about how it should be. Our supporters convey their messages not only through the meaning of their words, but also by their style of delivery. A soothing voice, a gentle embrace, or an accepting gaze goes beyond words in conveying their caring.

Tolerating Loss and Adversity

While these supportive functions do not resolve the stressful situation, they reduce the associated distress that often makes the pain unbearable. When the events surrounding the pain are irreversible, as in the case of death, or unresolvable, as with a divorce from an intractable marriage, the tolerance for the pain allows the grieving to proceed and the healing to begin. In other instances, in which there is some potential for problem-solving or conflict resolution, the tolerance for the pain allows us to face our dilemma and plan how we are to deal with it. In either case, the comforting function is often an essential step in allowing ourselves to face the pain so that we can understand it.

The Understanding Role in Fostering Wisdom

By understanding pain, we discover its meaning. Meaningful pain is generally more bearable than meaningless pain. We give it a name, we define it, and in the process we limited its scope. Thus, understanding is a second important function in developing our capacity to bear pain.

Pain as a Warning Signal

Through this process we come to view pain not as a feeling state to avoid. Rather, stress serves as a signal that all is not right in our world. It calls out that something needs adjustment. That change might be internal (e.g., grieving a loss or adjusting our expectations). Or it may be external (e.g., confronting a task or addressing a conflict with another). With such an outlook, we face our emotional hurts, determine the events which caused them, explore our perception of these events and our expectations surrounding them, identify our characteristic style of response to them, and to decide whether that approach is the most helpful. This process is one of redefinition and discovery of ourselves as well as of our personal worlds, whether the changes be related to some loss or gain or a reorganization of our lives.

Getting Support for Self-discovery

This self-discovery can at times be an exciting process, yet often is a humbling one. Either way, it is quite difficult to conduct by oneself, as we have difficulty stepping outside of ourselves to get an overall perspective on a situation that includes us in it. Others can help this process along by sharing their perception of us, revealing to us what is hidden by our own blind spots, what is out of focus, and what is distorted, whether positively or negatively. They can help us to discover how our response styles impact others and affect the problems we face. We can then decide whether that effect is likely helpful or harmful.

When Understanding Reinforces Acceptance

The understanding function does much to amplify the supportive function. By seeing the overall perspective we may not be quite so harsh in blaming ourselves. With a clear view of what is, our distress may not be as aggravated by our sense of what should be. We may better appreciate our values and principles as useful guides for living, rather than as universal laws upon which we can stake our security and well-being. We may view the problem more positively, as a potential growth experience, not an obstacle that blocks our path.

Cultivating Emotional Wisdom

Understanding helps us develop insight into ourselves and our world, yet without compassion it remains an intellectual exercise. We can experience our world and ourselves in subtle complexities. Multiple perspectives gives our world depth. We can see not just in black and white, but in various shades of gray.

Coloring our World

But what about color? This is where feelings have a second function: besides the role of signaling a disruption in our lives, they also enrich our experience. In an earlier article, I use the analogy of a prism to describe the process of sorting out the various emotional components of stress: that this exploration separates out the “white light” of stress into the various emotional hues. In fact, our idioms for our emotions have often assigned colors to various feelings – the red heat of passion, the yellow of cowardice, the blues of sadness, being “green with envy.” This process helps us to recover a more colorful picture of ourselves than presented with the general description of being tensed up or stressed out. This colorization of our experience with feelings enriches our lives and complements the definition and articulation provided by our intellectual understanding and insight.

From Physical Feelings to Emotional Feelings

Yet it is primarily through body sensations that our experiences attain their distinctive emotional tones. In connecting our various tactile, visceral, and kinesthetic responses to the events, interactions, expectations, and relationships that arouse them, we convert physical feelings into emotional feelings. Having your “hair stand on end” in fear, being “sick to your stomach” in disgust, and “getting all choked up” in sadness are more than mere figures of speech: they refer to emotions deeply felt in our bodies. A variation of the parental “tell me where it hurts” can help us to recognize the emotional components in our reactions to stressors. Thus, understanding from others helps us to associate our feelings states with the events and relationships in our lives in a way that colors and embodies our experience, making our lives richer and more meaningful in the process.

The Encouragement Roles in Fostering Courage

The functions of compassion and understanding outlined above help us to adjust to our world. We do so by accepting the limits of our influence in this vast world we encounter. Yet we not only respond to our environment, we exert influence over it. Understanding not only deepens our appreciation of our world, it helps us act on our surroundings. We can get what we need from it, and reduce or eliminate threats from it. Insight does not produce such changes per se: it must be put into action to effect change.

Managing Risk

Yet such actions come with a risk: if they did not, then the warning signals of our emotional reactions probably would not have gone off. Usually there is some conflict involved – we balk at pursuing our desires because of some real or potential cost. Understanding can help to put these risks in perspective, but they do not eliminate them. Insight may suggest to us what we need to do to improve our lives, but we still need courage to make these changes, and the encouragement of others can be helpful here. Others are helpful when they stick by us, continuing to urge us on when we balk, retreat, or simply get stuck. The motivational function primarily encourages us to take the necessary, often risky and unpleasant steps required to resolve a conflict or problem causing us stress.

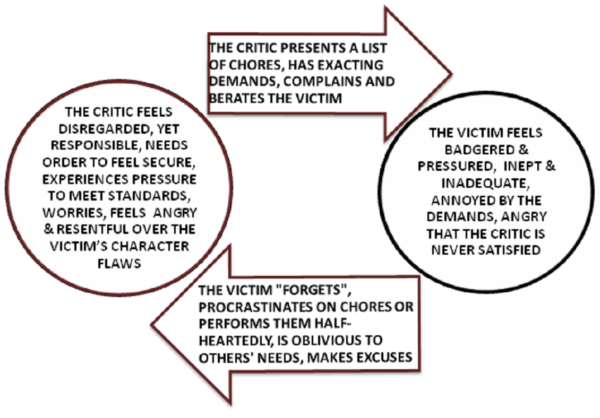

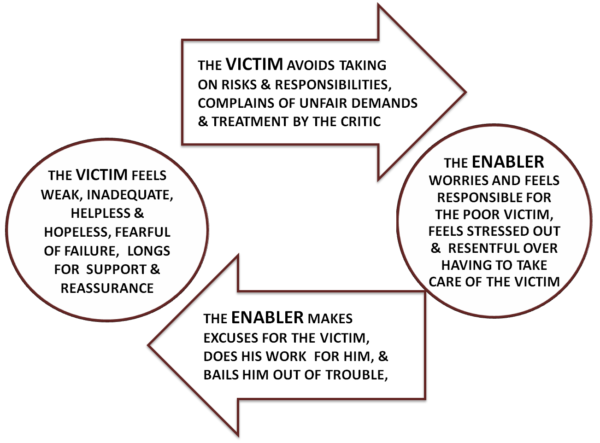

Balancing the Three Supportive Functions

The Serenity Prayer suggests the importance of finding a balance among the three supportive functions of soothing, encouragement, and understanding. An excess in any one element can be harmful to overall functioning. An overly soothing approach without understanding the issues or encouraging action can foster helplessness and dependency. This is particularly problematic in facing (or avoiding) situations for which action is required. An emphasis on understanding without adequate soothing may foster an intellectualized approach similar to Mr. Spock’s demeanor on Star Trek. An accompanying lack of encouragement may lead to an intellectual immobilization involving worry and rumination, similar to that dramatized by Shakespeare’s Hamlet.

A encouraging role may lead to action which lacks an appreciation for the subtleties of feelings, whether one’s own or those of others. It further is less appropriate in those situations of loss for which there is no adequate remedy except acceptance. These various examples of imbalances of support should show the need for a balanced approach that fosters thought, feeling, and action in response to emotionally tinged situations.

Of course, the particular demands of a situation will recommend emphasis of one approach over another. Some call for valor, others for compassion and sensitivity, and still others for restraint and deliberation. Another factor concerns the personal style of the person needing support. Here, it is often helpful to “play to the person’s weak suit.” This approach encourages balance by supporting the function that is typically underutilized.

Internalizing the Three Supportive Functions

Of course, we can’t always count on others to be by our sides as we deal with our stress. Nor should we expect that. Throughout our lives, we developed our own abilities to resolve our stresses. Much of this we accomplished by internalizing the supportive functions provided by others. First, we learned to comfort ourselves by conjuring up the supportive demeanor of our caretakers in their absence. Second, we gained perspective on situations by asking ourselves how our mentors would have viewed them. And third, we mustered our courage and took risks by imagining the urging of our coaches. We can now conjure up these presences consciously and deliberately. And even if we don’t, they still remain a potent voice in the background as we face our challenges.

When Doing Less Is Doing More

Others can help us to internalize these functions by not doing too much for us. Sometimes doing less is actually doing more. Our supporters may ask us how we can comfort ourselves in the meantime rather than coming over at 2 a.m. They may simply provide a sounding board to bounce off our own ideas, rather than defining the situations for us. They may ask us to consider our options, rather than giving us direct advice. Often we simply need someone to bear witness as we bare our souls in order to bear our pain.

Finding Balance in Interdependence

By internalizing the supportive functions of comforting, understanding, and encouraging, we cultivate our serenity, wisdom, and courage. We can better cope with our various emotional challenges with greater self-reliance and confidence. Still, it is not necessary, or even preferable, that we become totally self-sufficient. Rather than pursuing the ideal of independence, perhaps interdependence is a better goal, involving mutual support with others. We can still rely on others who may be farther along. And through their limited support, we can further develop our own capacity to bear our pain and stress. And in turn, we may serve as mentors, comforters, coaches, teachers, and parental figures for others.

The Intimacy of Reciprocal Support

Yet it is when the support is reciprocal that the special treasure of emotional intimacy unfolds. We then expose our private fears, doubts, and feelings to the caring of others, and care for theirs in return. This reciprocity offers depth, meaning, and strength to our lives in a way that total independence cannot achieve. On the broader scale, this mutuality of support fosters a sense of family, fellowship, and community. The balance between self-care and mutual interdependence with others promotes a healthy balance between individuality and belonging. This strengthens both our personal identities and our ties to others.