The current post identifies features of the Victim role and explores strategies for escaping this role. This draws upon the vicious cycle patterns addressed in a previous post, including Steven Karpman’s Persecutor – Victim – Rescuer cycle, cited in Games Alcoholics Play, by Claude Steiner. Most people are probably familiar enough with the Victim role so that it needs no introduction. If you haven’t fallen into that role yourself, you no doubt have encountered others who have. Or perhaps you have been cast in the complementary role of either the Oppressor or the Enabler in dealing with the Victim role. Of course, your familiarity with the subject won’t stop me from sharing my ideas about it.

Defining the Victim Role

The Victim role represents a particular response to suffering. This might be described through the questions, “Why is this happening to me, of all people?” and “What did I ever do to deserve this?” Implied in such questions is an assumption that life should be fair, and that we should get our just desserts without having to struggle for them. This sentiment is so common that Rabbi Harold Kushner wrote an entire book, Why Bad Things Happen to Good People, to address it.

The Victim Role in Relation to the Oppressor Role

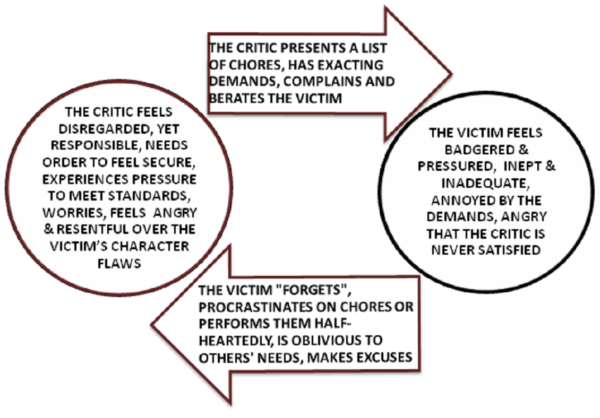

While the Victim role is sometimes adopted in reaction to events such as illness, accidents, and natural disasters, more often it is a response to the actions of others who are seen as intentionally abusive or unjust. This frequently involves establishing relatively enduring interaction patterns between the Victim and the Oppressor, as discussed in my page, Vicious Cycle Patterns in Relationships 2.0. Below is a diagram illustrating a common interplay between the Victim and the Critic, a relatively benign variation on the Oppressor role.

Here, Victims view their Oppressors as powerful and controlling, and in turn see themselves as powerless, helpless, and hopeless. These perceptions often serve as self-fulfilling prophecies, as they encourage Victims to practice avoidant and accommodating styles of dealing with conflict in relationships. In the process, other styles for dealing with conflict get neglected, resulting in a deficit of assertiveness and conflict-resolution skills: if you don’t use it, you lose it. In turn, the lack of such skills makes one all the more vulnerable to oppression by others.

Self-empowerment as an Escape Plan

The above description of the Victim role suggests self-empowerment as a means for escaping the role. This typically involves a willingness to engage in conflict rather than avoiding it or capitulating to the demands of others. Commitment to this approach is only a start – empowerment requires working smarter, not just harder. Not only can we work toward mastering the different interpersonal conflict strategies, addressed in a previous post, but we can also develop our understanding of when each is appropriate. Just as in football, where each side runs different plays depending on the game’s circumstances and the anticipated play of the opponent, strategy counts in conflict resolution. Perseverance counts, too: note that wars have been won even when the majority of the battles have gone to the other side. It is prudent to choose our battles, and to retreat in order to fight another day.

Knowledge is Power

Holding our own in conflicts may well depend upon our understanding not only of our adversaries, but also of ourselves. By understanding our adversaries, their weaknesses as well as their strengths, we can better judge when and where to use leverage effectively, and when and how to propose compromises from a position of strength. Stephen Mitchell’s translation of the Tao Te Ching notes the risk of underestimating one’s adversaries, such as by viewing them as evil. Such a simplistic perspective may blind us to the complexity of their perspectives and motivations, thus placing us at a disadvantage. Perhaps an even more difficult challenge is understanding ourselves: the Gospels note Jesus observing how it is easier to spot the splinter in another’s eye than to see the beam in our own. It is also quite helpful to understand how our interpersonal styles interact with the styles with others. My webpage, Vicious Cycle Patterns in Relationships 2.0, explores how certain common roles tend to interact with one other in a vicious cycle pattern. It offers some general suggestions for escaping the vicious cycle roles, regardless of the particular role one has assumed.

Shifting the Balance of Fight vs. Flight

Once one understands various aspects of a conflict, one can then put this understanding into practice through active engagement with one’s adversary. Here the motivational factor is quite relevant, with anger and fear being basic emotions involved. Anger charges us up to confront our adversaries, while fear serves to mobilize us to flee to escape danger. In evolutionary terms, our biological system is wired for a Fight vs. Flight reaction, which is appropriate for survival in life-or-death situations, but is excessive for most conflicts in civilized society. As we become more knowledgeable and skillful in dealing with interpersonal conflict, we become better able to stand our ground and assert our claims. Here, intense fear and anxiety can get in the way of this process by supporting old patterns of avoidance and submission. Anger can serve to override our fears and mobilize our active engagement in conflict, yet its intensity can be disruptive to the processes of negotiation and conflict resolution. Like steel, anger must be tempered to be used effectively. One strategy to accomplish this involves the use of meditation or other relaxation techniques to reduce the intensity of emotions from “so mad you can’t see straight” to a more moderate level.

Challenging the Attitudes That Incite Impotent Rage

In confronting our anger, we should recognize that our anger can be incited to rage not only through our more primitive Fight vs. Flight reaction, but also through our more advanced thought processes. This issue is addressed in a previous post, When Thinking Distorts Feelings. The post also presents a strategy for challenging some of the attitudes and underlying assumptions that fuel the fire of emotions, often to the point of their being disruptive rather than helpful (hence the term, “impotent rage”). By putting our anger and anxiety into proper perspective, we are better able to assert ourselves, rather than either going ballistic with rage or capitulating to our adversaries out of fear.

Developing a Positive and Realistic Perspective

There are other attitudes and expectations that often discourage us from asserting ourselves effectively in conflict. For one thing, it is pretty common to get discouraged when we stumble in our efforts to assert ourselves. We may need to remind ourselves that we can expect to make mistakes as we are practicing our newly learned assertion skills. We can reassure ourselves that these are only failures if we give up on the process. Furthermore, it helps to recognize that we can learn more from our mistakes than we can from our successes, unless we are blaming ourselves too harshly. It is also reassuring to know that progress is seldom linear, with it often involving two or three steps forward, followed by one or two steps back. We may also need to give ourselves permission to choose our battles, so that we might “live to fight another day.” We can also console ourselves with the recognition that wars have been won even when most of the battles went to the other side. Strategic retreat can be a valuable tactic, as long as it does not turn into unconditional surrender. Unless we adopt these attitudes, we run the risk of falling into the Critic role with ourselves, thus becoming “our own worst critics.”

How Do You Spell Relief?

Dealing with conflict is often a stressful experience, and strategic retreats to gain temporary relief can be valuable for sustaining our efforts. Here it is important to distinguish healthy outlets from those that actually “recycle” stress by providing temporary relief while worsening the overall situation. The latter often involve activities such as abusing substances, gambling, compulsive shopping, pornography, and comfort eating. Even when these outlets are pursued for strategic retreat, their emotional numbing and distraction often result in unconditional surrender through subsequent avoidance of the conflict. Furthermore, these outlets often give the Critic more ammunition with which to judge and blame the Victim, thus placing the Victim at an even greater disadvantage. Healthier outlets are available, though, with these generally fall into the categories of relaxation, recreation, exercise, and expression.

The Victim Role in Relation to the Enabler Role

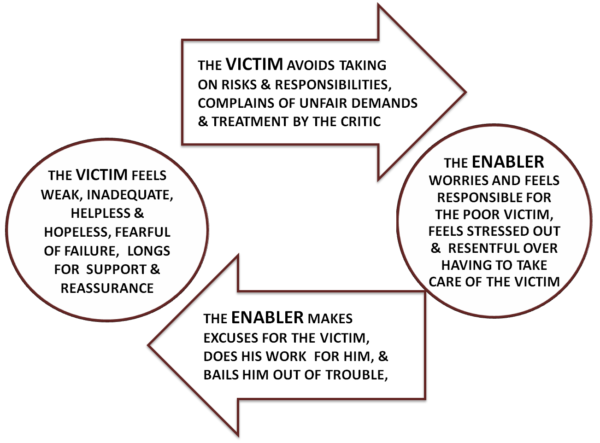

Thus far, the Victim role has been defined in relation to the Oppressor role and its variants, such as the Critic, the Persecutor, and the Abuser. The Victim role is also defined through its interaction with another interpersonal role, that of the Rescuer or the Enabler, with this pattern diagrammed below.

In this particular pattern, Victims express themselves through complaints about unfair conditions in their lives. They frequently seek out some tangible support or relief. This may not be explicitly stated, and often does not need to be, as Enablers are ready to volunteer support without even being asked for it. The sought-after relief may take many forms: provision of a safe haven, advocacy in defense of the Victims, mediation to resolve the conflict, protection from the wrath of Critics or Persecutors, concealment of mistakes, accidents, or wrongdoings, or completing the Victims’ responsibilities for them. While Enablers practice and develop their own assertion, advocacy, and communication skills in fulfilling these functions, Victims are relieved of this responsibility and thus fail to practice and develop these skills for themselves. This leaves them less competent and all the more dependent on the generous support of the Enablers, as well as more susceptible to the scorn of the Critics.

The Escape: “Please, I Need to Do This Myself”

It should be fairly obvious from the above discussion that one means of escaping the Victim role is to resist seeking support or relief from Rescuers, when we are capable of fulfilling these functions for ourselves. This also involves declining the unsolicited offers of those services, as well. That may require considerable self-discipline: why go through all that hassle when someone else will do it for us? This does not mean that we cannot accept someone’s support, as long as we retain responsibility for our position. Taking this approach provides the practice required to develop competence, earn credibility, and empower ourselves.

Complaints: Communication without Personal Vulnerability

In voicing their complaints to their Enablers, Victims often focus on external circumstances, rather than sharing their own personal experiences. In doing so, Victims claim the moral high ground in focusing on the abusive actions of the Critic, often without addressing their own shortcomings or the legitimacy of some of the Critic’s complaints. They often overlook their own passive-aggressive behavior, avoidance of conflict, and reluctance to challenge the Critic’s authority, all of which feed into the vicious cycle. By focusing on the faults of the Critics, Victims deflect attention from themselves, thus reducing the personal vulnerability involved in sharing their own anxieties, insecurities, and shame.

Beyond Complaining and into the Realm of Relating

We can escape the Victim mindset by sharing how we are feeling and doing, rather than just complaining about external events. This involves focusing on what is, rather than on what should or shouldn’t be. Being open about our fears and insecurities requires both humility and trust. Admitting our limitations may be humbling, but it helps to minimize the humiliation that comes with others recognizing our shortcomings before we acknowledge them. Opening up requires trust both in our confidantes and in ourselves: trust in the other to respect our feelings and honor our privacy, and trust in ourselves to cope effectively with those occasions when our confidantes lets us down in one way or another. While complaining about our situation may bring Enablers to our rescue, expressing our feelings is more likely to elicit compassion from our listeners. In the long run, being cared for is likely to be more beneficial than being taken care of. A further feature of open sharing is the experience of gratitude for the other’s compassionate presence. Not only can gratitude help us not to wallow in the role of Victim, but it can also encourage our confidantes to feel appreciated for their compassion. This, in turn, could help to discourage the confidantes from assuming an Enabler role that is detrimental to our growth. All of these developments help to shift the emphasis of the relationship from using the other for our own needs to that of relating to one another.

Emotional Intimacy Is a Two-way Street

Note that relating to one another is a two-way street. This requires the willingness to listen to others as they recount their struggles, as well as sharing our own. This in itself can be quite helpful for stepping out of the Victim role, as we can come to realize that our own struggle with oppression is not all that special. Furthermore, we may be inspired by hearing others’ accounts of how they overcame instances of abuse, neglect, or unfair treatment. Another benefit is in feeling good about ourselves for our compassionate listening to another’s plight. Yet perhaps the most valuable impact is the development of emotional intimacy, as both we and others allow ourselves to be vulnerable in sharing our personal struggles, which allows for compassion and gratitude for one another.