You may have great techniques for relieving stress, but how are your strategies for handling the stressors causing the stress? Using meditation, yoga, exercise, venting, or just plain relaxation to relieve stress is all fine and good. Even so, you’ll likely continue to encounter stressors throughout your daily activities and social interactions. And just where does that relief get you, if you continue accumulating stress? You may feel that your life is a revolving door, facing the same challenges day after day. Or worse yet, you may feel like a hamster on a treadmill, unable to keep up with your accelerating pace. If so, it only makes sense to develop and practice effective strategies for managing your recurring stressors.

First, a Matter of Perspective

Before focusing on the different types of stressors, it is helpful to recognize a factor common to all stressors. That is, the actual situation doesn’t determine the intensity of our stress, as much as our perception and interpretation of it does. In other words, we can make a mountain out of a molehill. It’s simply a matter of perspective. While this insight is a cornerstone of the cognitive behaviorism school of psychology, it is no new revelation. Epictetus shared this wisdom with his contemporaries back in the days of the Roman Empire.

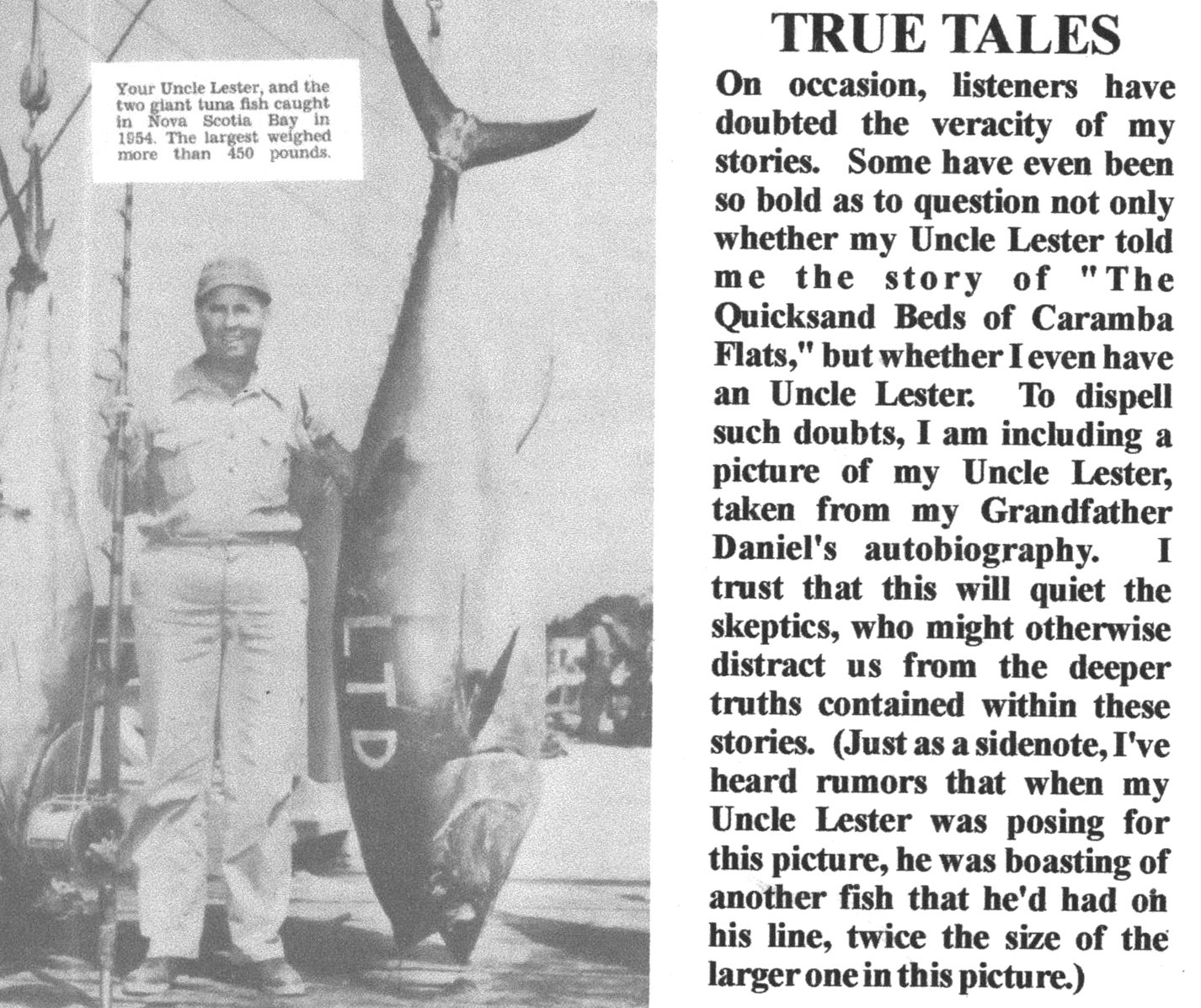

For most of you readers, this article serves as a reminder for what you already know. You may simply have found yourself swallowed up in the mire of a particular crisis. Here, a simple story, such as my Uncle Lester’s The Quicksand Beds of Caramba Flats, can help regain perspective. Or various sayings might help. Do we see the glass as being half-full or half-empty? Can we see the silver lining of the dark cloud? Such analogies and metaphors can help us regain our firm footing when we find ourselves on shaky ground. Now, we can consider the various strategies and techniques for handling the different types of stressors.

Different Types of Stressors

If you are like most, your stress comes from a variety of sources. It’s unrealistic to expect the same strategies to work well in all situations. Thus, it can be helpful to identify guidelines for handling some common types of stressors. That is just what this article proposes to do. For this task, I have compiled a list of four types of stressors, each of which suggest different approaches. These include Workload, Problems, Conflicts, and Losses.

Workload

Workload consists of our various chores, tasks, and demands. These stressors serve our needs and wants and our various obligations and responsibilities to others. They often involve satisfying direct or implied contracts (e.g., work for a paycheck, sharing household responsibilities, obeying laws). Here the work is pretty straightforward – we know the routine, and the main stress is the sheer amount.

Problems

Problems are aspects of our workload which are not so straightforward. These stressors involve certain complications that must be resolved to meet our needs or to satisfy our obligations. Sometimes the solution to problems is simply a matter of acquiring the needed knowledge and skills. At other times, it involves developing a game plan of strategies and tactics for applying this knowledge and skill.

Conflict

The stressor of Conflict is a particular type of problem, one with opposing and mutually exclusive objectives. In other words, you can’t have it all. We can further break down conflict into two types, internal and interpersonal.

Internal Conflicts

Internal conflicts are those between our own needs and wants. These often involve pairs of opposing values, such as security vs. freedom, order vs. spontaneity, and individuality vs. belonging. We might consider them as paradoxical dualities, as they do not lend themselves to clear-cut, rational solutions. In other words, logic will not determine which value should prevail. Rather, the resolution of these stressors typically requires a balancing or trade-off between the opposing values.

Interpersonal Conflict

Interpersonal conflicts involve a clash between our needs and wants and those of others. Even in the best of relationships, we will differ with our partners in terms of our goals and expectations.

Loss

The stressor of Loss involves our no longer have access to the people, things or events that are important to us. Such losses may be permanent and irreversible, as in the cases of death, destruction and severe injury. Or they may be only temporary, though still posing significant difficulties for us. We may lose actual people or tangible possessions, or our loss may be more abstract. Our self-esteem and reputation are examples of such abstract losses.

The Perspective of This Approach

The forthcoming guidelines are not particularly profound – “they’re not rocket science.” Rather, they offer practical reminders for when we get “so mad (or sad, anxious, etc.) that we can’t see straight.” Although presented from my own particular perspective, they are not original. I call upon the Serenity Prayer to sort out the types of stressors in terms of change and acceptance:

“God grant me the serenity to accept the things I cannot change, the courage to change the things I can, and the wisdom to know the difference.”

Rheinold Niebuhr

Within this framework, workload consists of those stressors that we can resolve (with sufficient courage and commitment). Losses are those that we cannot change, but must accept (hopefully with some serenity). Problems are those that we are not yet sure whether or how we can work them out (thus, requiring wisdom). Conflicts are those stressors that typically involve some trade-off or balance between change and acceptance. Each type poses particular demands and requires particular strategies, skills and attitudes to resolve the stressors.

The Stressor of Workload

Issue:

The sheer amount of work, responsibilities, tasks, and demands

Challenge:

To complete the various tasks and responsibilities in a satisfactory and timely manner

Strategies & Techniques:

- Organize – make a list, breaking the task down into manageable parts

- Prioritize – decide which tasks are essential and urgent, and which are less important

- Plan which tasks to tackle first, which to save for latter, and which to drop altogether

- Establish a reasonable schedule you can stick to

- Start work, one task at a time

- Pace yourself

- Delegate responsibilities, contract out to others

- Check the items off your list as you complete them, to monitor your progress

- Give yourself intermittent rewards after completing the different steps or stages – not before!

Pitfalls:

- Feeling overwhelmed, perhaps even unfairly victimized

- Self-criticism and blaming

- Procrastination and avoidance – breaks become unconditional surrender, rather than strategic retreats

- Demands and tasks accumulate, making the workload feel all the more oppressive

- Coping skills atrophy, or weaken, through non-use (“If you don’t use it, you lose it.”)

The Stressor of Problems

Issue:

The Workload is not simple and straightforward. Rather, it requires developing a new approach or modifying an existing one in order to get the task done.

Challenge:

To find a solution to the problem(s) thwarting completion of the task

Strategies & Techniques:

- Take time to develop your own knowledge and understanding of the problem – to find an answer you must first understand the question.

- Remember that working hard is a good strategy for workload, but working smart is generally better for problems

- Step back and take a break to get a fresh perspective, especially if you “can’t see the forest for the trees.” (Make sure this is only a strategic retreat, not an unconditional surrender.)

- Seek out others’ expertise and guidance, perhaps even hiring a consultant

- Brainstorm: If “two heads are better than one,” just think what several can do.

Pitfalls:

- Tunnel vision – not questioning your own perspective – one definition of insanity is “taking the same approach and expecting different results”; finding a solution often requires looking at the problem in a different way (i.e., “thinking outside the box”)

- Working harder, rather than working smarter, thus “spinning your wheels”

- Negativity – adopting a negative outlook discourages a positive solution – “self-fulfilling prophecy” – rather, look at the problem as an opportunity to discover & practice new understanding and skills

- Complaining about how the problem shouldn’t be, rather than accepting it as reality and dealing with it

- Procrastination and neglect, which often allows it to get worse – in contrast to “a stitch in time saves nine.”

- Avoidance of problems interferes with developing positive problem-solving skills.

The Stressor of Conflict

As we have addressed above, conflict can be either internal or interpersonal. Actually, this stressor typically involves both dimensions. This is chiefly related to the tension between being an individual and belonging to a group. It is here that our concern for our own individual well-being and our caring for others collide. Only if we were totally selfish or totally selfless would we escape this internal tension.

Interpersonal Conflict

Issue:

A disagreement with someone prevents you from getting what you want, poses a hardship, keeps you from completing your work effectively, or disrupts your relationship

Challenge:

To resolve the conflict and restore harmony. This is part of a broader, ongoing challenge: that of striking a balance between looking out for your own self-interests and demonstrating your commitment to the relationship and caring for the other. The only time that you really proclaim you own sense of individual self-worth is when you take a stand in opposition to someone else. And the only time that you really demonstrate your caring for the other is when you sacrifice your own self-interests for their benefit. Through the ongoing series of conflicts, large and small, we are perpetually fine-tuning the balance between individuality and relatedness.

Strategies & Techniques:

- Two fundamental prerequisites for resolving conflict are safety and respect: without safety, any resolution is achieved under duress, and resolution without respect is often a hollow victory.

- Be flexible in your styles of dealing with conflict. You wouldn’t construct a piece of furniture with just one type of tool. When various styles are used in balance and moderation, they typically are adaptive. Excessive use of any one style may be counterproductive.

- Common styles of dealing with conflict are Avoidance, Confrontation, Accommodation, Cooperation, and Collaboration. (These styles are discussed in more detail elsewhere.)

- Conflict resolution involves three basic components: self-expression, active listening, and negotiation.

Listening

- Usually both sides need to have their feelings heard before they are ready to consider possible solutions.

- Keep an open mind: just as your point-of-view make perfect sense to you, so, too, do your adversaries’ perspectives make sense to them. It is unrealistic to expect that a conflict will be worked out only from your perspective. Afterall, no one’s going to let you have the home field advantage all the time. Besides, discovering another perspective expands your horizons.

- If you want your partners and adversaries to consider your perspectives, you’d better demonstrate your willingness to listen to theirs. It’s not enough to comprehend their point-of-view. You must demonstrate your understanding of it to them. It’s even better if you can show that by “reading between the lines” – that is, if you don’t do it in a critical, defensive, or controlling manner.

- Listen to your partner before expressing your point of view. That way, you’ll have more of their undivided attention.

Expression

- Your partner or opponent is not a mind-reader: the more clearly you can state your position and its rationale, the better your chance for a fair settlement. Define the problem from your viewpoint, describe how it is affecting you, state your expectations, and perhaps indicate the incentives for your partner agreeing to your proposal.

- Incentives probably work best if they are concessions you are willing to make or are natural consequences of the agreement. Otherwise, they may convey a sense of manipulation, bribery, extortion, blackmail, etc.

- Expanding the discussion to include other complaints to justify your position tends to make the negotiations complicated and contentious. While it can be helpful to put your position in a broader context to enhance mutual understanding, it is often better to address one issue, or just a few related issues, at a time.

Negotiation

- Negotiation needs to take both perspectives into account. While compromise often involves a “50-50″ solution, in which both sides get some of what they want, collaboration can strive for more of a “win-win” situation, in which both sides can get more than half. This involves the additional use of problem-solving techniques, discussed in the previous section.

- Incentives probably work best if they are concessions you are willing to make or are natural consequences of the agreement. Otherwise, they may convey a sense of manipulation, bribery, extortion, blackmail, etc.

- Know the rules of the game: if your adversary is playing his or her hand with the cards close to the vest, and you are laying your cards on the table, you are not going to win your fair share of poker hands.

Pitfalls:

- Blame and focusing on whose fault a problem is accomplishes little more than creating animosity. It’s often not necessary to know how a problem got that way in order to fix it.

- Complaining may be a safer form of communication than expressing one’s feelings, but it tends to foster defensiveness and counterattacks.

- Trying to find a solution before your partner expresses their feelings may convey an attitude that you don’t care about them.

- Insisting on getting your way all the time puts off the other person, reducing the chances of a resolution, or making the settlement a hollow victory.

- Accommodating or giving in to others regularly usually leads to them taking you for granted and to your feeling resentful.

- Avoidance of conflict may involve losing by default – giving in rather than addressing the differences.

- Avoidance of conflict prevents you from developing the skills needed to negotiate a favorable settlement for yourself. This tends to give others an advantage in future conflicts.

Internal Conflict

Issue:

Life frequently involves internal conflicts, in which something must be given up. Often these conflicts are unavoidable, as they involve an inherent paradox of life, generally requiring some trade-off. Security vs. freedom, order vs. spontaneity, and individuality vs. belonging are examples of such paradoxes.

Challenge:

To reconcile opposing needs, feelings, urges, values, and interests in ourselves, in order to achieve an integrated self, that balances and reconciles opposing values and perspectives.

Strategies & Techniques:

- Values clarification: identifying the various implicit values on each side of a conflict situation.

- Recognizing conflicts as opportunities to clarify and articulate our basic values, thus helping us to know ourselves better.

- Identifying the pro’s and con’s on each side of a conflict situation, weighing the likely and possible consequences of a particular resolution to a conflict.

- Recognizing that a healthy resolution of a conflict often involves a trade-off between competing sides, rather than having an either-or or all-or-none resolution.

- Realizing that something must be given up in the trade-off, and perhaps going through a grieving process.

Pitfalls:

- It is often tempting to “project” one side of an internal conflict onto someone else, so that it is experienced as an interpersonal conflict, rather than an internal one. For example, baiting others into condemning one’s drug abuse might distract attention from one’s own shame over using.

- “Projecting” one side of a conflict onto others allows ones to pursue one side of the conflict, perhaps as an act of rebellion against their censure.

The Stressor of Loss

Issue:

Something or someone that has been an important part of your life is no longer available,

Challenge:

To accept a loss, to honor the positive in what you’ve lost and to forgive the negative, to let go and move on with your life. The loss may be something tangible (e.g., death of a parent or sibling, divorce, job loss, disability from chronic illness) or something more abstract (e.g., self-esteem, reputation, respect, honor, trust, sense of identity). Whichever it is, we are called upon to give up something that can’t be entirely fixed or replaced. Or we may simply come to a realization of the natural limitations and paradoxes of life (e.g., not being able to “have our cake and eat it, too”).

Strategies & Techniques:

- Expressing sadness and grief over the loss, rather than simply complaining

- Recognizing the difference between grief and self-pity

- Utilizing social support, allowing others to bear witness to our mourning

- Dealing with the loss emotionally, not just intellectually

- Working through the various phases of the grief process (denial, anger, bargaining, depression, acceptance), rather than distracting yourself from this work

- Letting go, both of the longing to regain the lost person or thing, and of any anger and resentment over the loss

- Honoring what you’ve gotten out of what you have lost. This work at incorporating the positive qualities into your own life serves as a remembrance for what or whom you have lost.

- Establishing a balance between healing the wound of the loss and moving forward in your life. Over time, the balance should be gradually shifting toward the latter.

Pitfalls:

- Getting stuck in longing for the past, or in bearing a grudge or resentment over what was taken away from you, rather than letting go of the lost person, thing, or quality

- Confusion between complaining and grieving. Complaining involves holding onto ones grievances, rather than letting go.

- Confusing sadness with weakness. Ironically, we best regain our strength and resiliency by giving into our sadness and working through the grief process.

- Toughing it out, not wanting to let anyone see you sweat, especially sweating tears

- Numbing oneself to avoid the pain of the loss, thus staying stuck in unresolved grief

- Wariness over establishing a similar involvement in the future, to avoid a similar pain and loss

Summary

The above discussion utilizes the Serenity Prayer in sorting out four types of stressors and recommending strategies for each. Many of these tips are common sense and likely already familiar. Thus, these lists serve as useful reminders of helpful outlooks and skills in the midst of stress.

Additional Resources

In calmer times, more extensive exploration of this topic can strengthen these perspectives. Thus, the strategies and techniques can be more readily available when called for. Such further discussions are offered in other posts on this website. Baring Your Soul, Bearing Your Stress goes into more detail with the Serenity Prayer to explore the use of expression and emotional support in coping with stress.

Internal Conflict

Two articles address the paradoxical nature of many internal conflicts. Living Rationally with Paradox: Staying Sane in a Crazy World, or Trying to Force a Round Peg into a Square Hole? addresses the limitation of logic in resolving such dilemmas. Muddling Down a Middle Path: Wading through the Messiness of Life suggests a balance or trade-off between the conflicting values.

Interpersonal Conflict

Other articles address interpersonal conflict. Dealing with Conflict in Relationships: The Art of Assertiveness goes into more detail on resolving conflict with close relationships. When Is a Conflict Not a Real Conflict? addresses when differences are due to misunderstandings, rather than actual conflicts. And Interpersonal Conflict Strategies explores the strengths and limitations of different styles of dealing with conflict, thus suggesting flexibility in one’s approach. Vicious Cycle Patterns in Relationships 2.0 delves into our tendency to get drawn into recurrent, unhealthy patterns with our partners.

Just One More Thing . . .

We often get trapped into viewing our stressors as obstacles that interfere with our lives. This typically leads to avoidance and its associated negative feelings, such as dread, resentment, and shame. Another option is to view stressors as providing opportunities to grow. Here, we can expand our perspective, develop our skills, and affirm our place in the world. Embrace the adventure!