Emotional burnout and compassion fatigue are common pitfalls among those of us who assume major Caretaker roles. Exhaustion, irritability, emotional numbness, and various physical complaints are warning signals indicating the need for better self-care. However, we often do not feel we have that option, as we see our own needs overshadowed by the needs of those in our care. We may develop a sort of tunnel vision, locked into a miserable path with no way out. What we had undertaken as a labor of love has evolved into a duty out of obligation, at times breeding an attitude of resentment. While there may be no appealing solution to this dilemma, this article proposes some perspectives and strategies that may offer some relief. It is likely that many of these ideas have been suggested to us previously and found lacking. Still, it is worthwhile to revisit these suggestions, reexamining and challenging our reservations and resistances to them.

The Caretaker – Dependent Relationship

It is obvious that the Caretaker role does not function in a vacuum: we need others to adopt a Dependent role in order to practice our Caretaking activities. We may assume the primary Caretaker role, or we may be called upon to take an auxiliary or backup Caretaking position. Our Dependents may have either acute or chronic needs which they are unable to fulfill for themselves. Some, particularly those with significant limitations and disabilities, may need considerable taking care of or doing for, while for others, caring for or being with will often suffice. Even with these differences, there is enough common ground to justify covering these variations from the same basic perspective, as I am doing in this article.

The Positive Impact of Caretaking on Both Giver and Receiver

Under ordinary circumstances, the Caretaker role is not just manageable, but also fulfilling. This undertaking may be longstanding, such as raising a family, or short-term, such as comforting a friend going through a temporary crisis. This role cultivates our compassion for others, strengthening the bonds of our relationship in the process. We also feel good about ourselves for helping others, especially when they express gratitude for our support. The Caretaking is obviously helpful to the Dependents, as well, particularly when it meets needs that they cannot resolve on their own. For those recipients capable of developing their self-care skills, this Caretaking gives them the time and the social modeling to become more self-reliant: why else would childhood last over a dozen years, until children are ready and able to move out on their own? And for those incapable of developing their own independent coping skills, the Caretaking provides a valuable safety net. Such is the case with children with severe developmental disorders or elderly plagued by dementia. Regardless of the Dependents’ potential for developing self-care, the Caretaker’s sacrifice and compassion helps them feel loved and valued.

Key Factors Supporting the Relationship

We can see that the interaction between Caretakers and the Dependents they support can be mutually reinforcing and mutually beneficial – a pattern which psychologist Paul Wachtel defined as a virtuous circle. Several factors shape the degree to which this interaction forms a relationship (i.e., it being enduring and recurrent). This pattern tends to persist to the degree that the Dependents experience ongoing and/or recurrent wants and needs that they cannot or will not seek to fulfill on their own. Another factor involves the particular Caretaker’s willingness and ability to help, as well as the availability and appeal of other available support options. The quality of the interaction also plays a key role: the attitudes and expectations expressed by both sides can be just as important as the tangible benefits of the support. The Caretaker’s success in satisfying the Dependent’s wants and needs plays an obvious role. Success will conclude the interaction for a given situation, yet will increase the likelihood for a repeat of the pattern when another need or want arises. The various factors affecting Caretaker—Dependent relationships are certainly more extensive and complex than described in this brief paragraph. Still, this summary suggests some strategies for addressing those times when the relationship is not serving the mutual benefit of both parties. The rest of this article will explore these factors in more depth.

When Demands for Caretaking Are Excessive

While Caretaking usually has benefits for both giver and receiver, Caretakers can get too much of a good thing. Circumstances beyond our control may intervene, with severe and enduring demands that wear us down. Caring for a parent or a spouse with dementia, or for a severely disabled child, for example, can pose a daunting challenge. Making matters worse, our care recipients may have little potential for growth and self-reliance, such that Caretaking is essentially a maintenance role, with no end in sight. In such situations, we may come to see ourselves as victims of circumstance, with no other option than total surrender to the Caretaker role.

Helping Ourselves so that We Can Help Others

It is when we are confronted with such challenges that we are most called upon to take care of ourselves – after all, we cannot be much help to others if we become overwhelmed and depleted. We can remind ourselves of the flight attendant’s instruction that in the event of loss of cabin air pressure, we should put our own oxygen masks on first, so that we can reliably assist our Dependents. We may need to do something as simple as reminding ourselves to breathe deeply when we feel the demands to help others sucking the air out of us. We have a word for when we take and release a deep breath automatically – it’s called sighing. And when we consciously take a series of deep breaths, it’s called meditation.

The Challenge of Looking Out for Ourselves

Such advice, to take care of ourselves first, sounds rather simple and straightforward – that is, until we try putting it into practice. Then, we brace ourselves for the challenge, holding our breaths and building tension. We are likely to meet resistance to our practicing self-care, at times from others who encourage our Caretaker role, yet most often and most intensely from ourselves.

The Caretaker Role as a Core Part of our Identity

The reluctance to practice self-care is prevalent among those of us who value the Caretaker role above all else. With this as the core of our identity, our self-worth rests upon a rather narrow criterion: am I helping others? This is in contrast to identity and self-esteem founded upon the broad array of our individual qualities, interests, attitudes, values, and principles.

The Temptation and Risk of Hiding behind the Caretaker Role

The Caretakers’ limited scope of their own interests and activities leaves them little common ground with their peers, often leading to a sense of disconnection or alienation. Perhaps for this reason, many of us who assume the Caretaker role actually prefer not to have attention focused on ourselves. Attending to others in need shifts the spotlight onto them and away from ourselves, thus alleviating our vulnerability of being visible to others. While this protects us against judgment and criticism, it also discourages others from having compassion for us. Instead, Caretaking allows us to experience compassion vicariously, through identifying with the struggles of others. Thus, we can avoid acknowledging our own needs, which could trigger a sense of inadequacy in our pursuit of self-reliance.

Is the Support Really Helpful to the Recipient?

While selfless concern for others appears rather noble at first glance, it has its downside. This intense need for service to others for a sense of self-worth discourages the Caretakers’ critical thinking. The question of whether others are unable to help themselves, or unready or unwilling to do so often goes unasked. Without an answer to this question, it is unclear whether the offered support would actually help the recipients or might encourage unnecessary dependency. In other words, while such support provides a sense of meaning and purpose to the provider, does it really help the recipient? As a folksy saying goes, “When the only tool you have is a hammer, everything starts looking like a nail.” Those with strong Caretaker cores to their identities are likely to relate to others, even their peers, as Dependents. As we shall discuss later, this approach limits the contributions of those assigned to the Dependent role.

When Selfishness and Selflessness Are Out-of-Balance

Unless we have a complementary role promoting self-care and self-advocacy, we tend not to affirm our own interests and activities beyond that of helping others. The Caretaker attitude, in promoting selflessness, devalues such self-affirming qualities, which are viewed as selfish, negatively valued, and often disowned. (In a broader sense, the common response, “I don’t know – what do you want to do?” exemplifies such an outlook.) The Caretaker’s deference to others is a recipe for disaster, leading to burnout and the eventual inability to help others.

The Broader Issue of Balance between Polar Opposites

Here it is helpful to put the selfish vs. selfless conflict in the broader perspective of the human condition. This duality is just one of several pairs of conflicting values which pose similar dilemmas for finding healthy approaches to relationships and lifestyles. The issue of self-interest, with selfishness and selflessness at opposite poles, is an example of what I call paradoxical dualities. These pairings of opposing values represent basic qualities of the human experience, if not of reality. Other dualities include order vs. freedom, belonging vs. individuality, being vs. becoming, and adventure vs. security.

Each polarity involves a trade-off: the more you have of one, the less you get of the other. A folksy saying captures the essence of the being vs. becoming conflict: “You can’t have your cake and eat it, too.” This refers to the choice between enjoying current pleasures or saving for the future. Of course, this is not a total either-or proposition, as you can have a slice of cake today and still have plenty some left over for tomorrow. The decision of where to slice the cake between today’s and tomorrow’s portions is one determined not by logic, but by a preference based on personal values. Hence, the term “paradoxical duality,” rather than “logical problem.” While logic provides no right answer for where along the continuum to cut the cake, we do have a basic guideline: positions at the extreme ends tend to be maladaptive, whereas those near the center tend to be healthy. This idea is by no means new, as Buddhism has advocated the Middle Path for centuries. (The ideas promoted in this section are explored in more depth in my earlier posts, Muddling down a Middle Path: Wading through the Messiness of Life, and Living Rationally with Paradox: Staying Sane in a Crazy World, or Trying to Force a Round Peg into a Square Hole?)

The Issue of Balance Applied to the Caretaker Role

Having addressed paradoxical dualities as a general theme of the human condition, we can now relate the insights more specifically to the issue of selflessness in the Caretaker role. Here, we can extend the cake metaphor: those committed to the pure and unmitigated Caretaker role do not cut the cake. Instead, they give the whole cake to their Dependents, whom they see as much needier than they. While Caretakers will partake of the table scraps, often there are no leftovers. This pattern is in contrast to a healthier one, where the Caretakers keep portions for themselves, as well as giving some away. And it also is important that Caretakers eat at least some of their cake to satisfy today’s hunger, rather than saving the entirety for a tomorrow that is always a day away. Otherwise, as they go hungry, they become less use to themselves and others. Symptoms of emotional burnout and compassion fatigue may be indicators of an unhealthy imbalance in favor of service to others. Still, we must recognize the warning signs before we are ready to take corrective action.

Modifying the Caretaker Role

Achieving the above perspectives on the Caretaker role can allow us to rein in our caretaking activities and to practice better self-care. Such shifts can help bring being-for-others and being-for-self into balance, supporting a healthier lifestyle.

Some Insights that Provide Permission for Self-care

Various insights help us to achieve this balance. Knowing that we cannot provide adequate help if we are running on empty provides some permission to tend to our own needs. Realizing that our having wants and needs is normal allows us to seek support and caring without feeling guilty or inadequate. When we recognize that protecting ourselves from potential judgment by others also discourages their compassion for us, we can decide to risk the vulnerability of exposing our needs, feelings, and insecurities. (We still need to exercise judgment in choosing our confidantes, as some can be rather judgmental of us.)

Practicing the Inverse Golden Rule

Those of us identified with the Caretaker role typically experience much internal resistance against taking care of ourselves before others, and even more reluctance to asking for and receiving help. We may express objections to being selfish or to being a burden to others. Here, we can practice what I call the Inverse Golden Rule, discussed in a previous post. This can be summarized as, “Do unto Ourselves as We Would Do unto Others.” We can ask ourselves what we are saying about our own self-worth when we consistently put others’ wants and needs ahead of our own. While we may voice affirmations of self-worth based upon our service to others, our putting others before ourselves sends a message that our needs do not count as much as theirs. When our Dependents hear this message, they may be less inclined to consider our wants and needs. Furthermore, such thorough caretaking sends a message to the recipients that they are entitled to such extensive care from us, such that they might take it for granted or fail to appreciate the toll their care demands. Its ready availability may also discourage them from developing both a broader support network and an ability to fend for themselves.

Getting Social Support

A second version of the Inverse Golden Rule can be stated as, “Allow Others to Do for Us as We Would Do for Them.” Just as we don’t expect our Dependents to care for themselves all on their own, we should not expect ourselves to do so, either. There are many support groups out there, such as for caretakers of Alzheimer’s patients and for family members of those addicted to alcohol and drugs. Here, we can share our stories with others who understand what we are going through, which helps us not to feel so alone and isolated with our burden. We need to monitor ourselves, though, as we might decline such help out of concern that seeking it out would pose a burden on others or entail neglecting our Dependents’ needs.

Allowing Others to Care for Us

When we hesitate to ask for support to avoid inconveniencing others, we can ask ourselves whether we would feel burdened by the same request from others. Usually, when I have asked others this question, I’ve gotten the response that it is no bother. They often note how attending to others’ feelings provides some relief from focusing on their own problems. Or they may report getting some comfort in knowing that they are not alone with their distress. Overall, they note feeling good about being there for others. If that is so, then why would we want to deprive others of the opportunity to feel good about their being there for us? That would just be plain selfish! This support is rather low-cost when the request is simply for understanding and empathy, rather than for tangible assistance. When that support is mutual, as in the support groups, we don’t feel so alone in our ordeal, and both sides win.

Guilt over Neglecting Others When Practicing Self-care

Self-care is particularly challenging when saying “yes” to ourselves means saying “no” to others, even if only temporarily. Perhaps it would not be sending a bad message to our Dependents that we have needs, too – just as long as we don’t do so out of resentment about Caretaking roles that we have taken on ourselves. Also, we need to be careful not to neglect ourselves by taking care of other Caretakers. Remember that mutual caring for one another is often helpful enough. Accessing social support with those who “get it” can help us to practice and develop balance between being-for-others and being-for-ourselves.

Acknowledging our Limitations

Realizing that there are limits to what we are able and willing to do can be a humbling experience, especially when we pride ourselves for our selfless giving. We may need to come to the realization that even though no one else in the world is willing or able to give the same quality of care that we can, plenty of others can offer adequate care, and adequate can be good enough (if we let it). Following the dictum, “If you want it done right, you’ve got to do it yourself,” is a guaranteed formula for burnout. This can turn a role of primary Caretaker into one of sole Caretaker. We need to ask ourselves whether going the extra mile is worth the added stress. This stress can lead to our resentment, which can contaminate our Caretaking, regardless of its quality of service.

Allowing Ourselves to Be Human

Exercising the vulnerability of acknowledging our struggles opens us up to the compassion of others, even our Dependents. This can help us to accept our doing what we can, even if it does not live up to our own high standards. We may have difficulty with accepting this support, though, particularly if we get compassion and empathy confused with sympathy and pity.

The Complementary Dependent Role

Thus far we have focused our attention primarily on one half of a social interaction pattern. Our Caretaker roles do not operate in a vacuum, but need others to adopt Dependent roles in order to function. Note that this is not a one-way street, but a back-and-forth dynamic process: “It takes two to tango.”

When Too Much Help Is Bad for the Recipients

Specific situations of intense demands on Caretaking that we have addressed thus far have involved extraordinary circumstances, such as raising a child with severe intellectual or physical impairment or dealing with a spouse or parent with dementia. Yet we are not always the innocent victims of circumstance when we become consumed by the Caretaker role. Instead, we may embrace this style as a primary means of relating to others in our lives, with this having often negative and sometimes devastating consequences.

Fostering Dependency

Our mode of being-for-others can function effectively only when others assume a Dependent role in relating to us. As overly diligent Caretakers, we quite naturally encourage that dependency in others: we train others to underfunction when we overfunction. This approach often involves the unexpressed attitude that they cannot take care of themselves, which may lead them to doubt their own abilities. Our dedication and sacrifice train them to expect an excessive level of care from us. They may become hesitant to try helping themselves or to turn to others for help, leaving the burden squarely on our shoulders. They may pull our guilt strings for doing anything less than what they are accustomed to from us. Our ready availability is doing them no favors when it discourages their self-reliance, their development of a broader support network, and their positive self-esteem. While accommodating their wants and needs may keep the peace temporarily, we could be “killing them with kindness.” This has literally been true, such as when prescription of opiates to relieve chronic pain leads to addiction and overdose, which has been a major reason for the deaths of thousands of Americans annually. Yet it is not just in such extreme cases that excessive Caretaking has devastating effects. The Caretaker’s repeated messages of the Dependent’s personal inadequacy, implied in their excessive caretaking, can erode their Dependent’s self-confidence and willingness to take risks. The subtlety of these messages, particularly when cloaked in good intentions, makes them all the more difficult to challenge.

The Enabler and Victim Roles

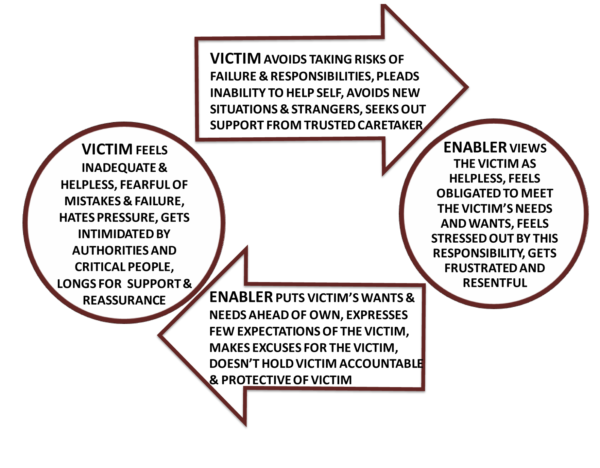

It is when the Caretaker role has such harmful effects that we define it as “enabling” behavior (i.e., encouraging dependent behavior that is ultimately counterproductive). Thus, we might consider the Enabler role as a particular unhealthy version of the Caretaker role, one which brings out the worst in the Dependent role. Similarly, we might identify the Victim role as a dysfunctional variant of the Dependent role, one which I have addressed at length in my post, Escaping the Victim Role. Here, the fundamental attitude is one of helplessness and pessimism, whether that might be in the face of challenging life circumstances or at the hands of Oppressors, who deprive Victims of their full rights. The Enabler and Victim roles are mutually reinforcing, resulting in their intensification through their escalating interaction. Dr. Wachtel has defined this interaction of mutually detrimental roles as a vicious circle, for which I am using the more familiar term of “vicious cycle.”

The Victim – Enabler Vicious Cycle

While the Victims’ demands may be rather frustrating, we should realize that our enabling trained them well to have their expectations of us, and it may require much effort to retrain them to be more realistic in their demands. We should also note that they have trained us to be responsible for them, and that we may need pointed challenges as to our involvement and our expectations, both for them and for ourselves. Through this process, we may come to realize that we expect too much of ourselves and too little of them. A conflict ensues when their demands for our support compete with our own wants and needs. This has all the makings of a vicious cycle pattern of relating:

- Conflict-based, involving opposing forces

- Complementary roles of the participants (e.g., the Enabler and the Victim)

- Repetitive nature of the interaction

- Failure to resolve the conflict

- Persistence of the roles, despite lack of success toward achieving a desired outcome

- Frustration of all the parties involved

Diagramming the Cycle

These general patterns are explored in more detail in one of my more popular blogs, Vicious Cycle Patterns of Relationships 2.0, which addresses several such patterns. The key point here is that the mutual interplay of these roles makes it difficult to escape the vicious cycle pattern, however distressing it may be. The diagram below illustrates two basic aspects of each participant’s involvement, for both the Victim and the Enabler. Inside the circle are the internal experiences, such as thoughts, feelings, attitudes, intentions, expectations, and perceptions. These are private experiences, to which the other has no direct access. At best, each can infer these experiences of the other from their outward expression, which is diagrammed inside the arrows. This expression includes actions, verbal communication, and nonverbal cues that others can perceive and interpret. Note that the diagram illustrates that one’s actions are not in direct response to the action’s of the other (diagrammed inside the respective arrows). Rather, the actions are responses to one’s own interpretations (diagrammed insider the respective circles) of the other’s preceding actions. When the contents of the circles and arrows are specified in sufficient detail, a review of the diagram should reveal how one’s outward expression leads to the particular inner experience of the other, and how one’s inner experience (i.e., interpretations of events) leads one to respond with the specific outward expression taken.

Victim – Enabler Vicious Cycle

General Guidelines for Escaping the Cycle

Once we have mapped out a diagram of our Victim-Enabler vicious cycle, we can work at freeing ourselves from the pattern. My previous article, Vicious Cycle Patterns in Relationships 2.0, offers some general tips in the section “Breaking Free of the Cycle.” Several of these can be applied to the Caretaker role. One particular guideline suggested by the diagram is to work on changing our own role in the cycle, rather than focusing on the others’ role. This runs counter to a natural tendency to focus on their Victim stance – after all, this is what usually bothers us. Furthermore, we can perceive their faults more easily than our own, consistent with a gospel passage that notes that it is easier to spot the splinter in another’s eye than the beam in our own. It is important to overcome this limitation, since we only have direct control over our own actions. Also, any attempts to change others not only disrespects their autonomy, but also tends to provoke their resistance. When we change our actions and communication toward the Victims, we no longer provide the cues that trigger their usual experiences and expressions. In essence, when we change our dance step, it motivates our partners to change theirs. If they don’t, some toes will get stepped on.

The Pitfall of Taking the Victims’ Reactions Personally

Another advantage of this particular way of diagramming vicious cycles is that it both identifies our interactions and differentiates my roles and yours in the drama. One of the common features of vicious cycles, such as between Enablers and Victims, is a sense of being consumed and losing ourselves in the chaos. One feature that contributes to this self-less experience is that of taking the Victims’ reactions to us personally. Doing so gives their Victim role power over us while undermining our own personal authority. This renders us less able to value ourselves based on our own experience and actions, as we long for the Victims’ appreciation and fret over their critical judgment and blame. This process encourages our Enabler tendencies, which in turn reinforces the Victim role.

Getting the Bigger Picture and Our Parts in It

Taking the time and effort to understand how the vicious cycle works and how we take part in it allows us to see ourselves more clearly in this highly emotional context. It also grants us an opportunity to understand and appreciate our co-participants in the vicious cycle better. To paraphrase a proverb from the Tao Te Ching, when we understand how the system (i.e., vicious cycle) works, we can have compassion for each member of it. A similar, more familiar saying notes how we “can’t see the forest for the trees.” The vicious cycle diagram helps to achieve a view of both. This exercise grants us a clearer picture of how our private experiences are influenced by others’ actions, and how our actions helps to shape others’ view of us.

The Path toward Individuality and Belonging

The vicious cycle diagram can be quite helpful in sorting out what is yours, mine, and ours, both in private experience and in outward expression. If you’ll recall, the earlier discussion of paradoxes included the dualities of individuality and belonging. Here, we face the paradox that our individual identities are established through our involvement with others, both those we agree with and those we oppose. As with other polarities, the more extreme positions are fraught with peril, where individuality poses the risk of alienation and belonging introduces the hazards of conformity. (This existential dilemma is rather abstract, and here I like to refer to a rather deep, but brief illustration of it, in the flake vs. drip dilemma.)

Finding Balance between Individuality and Belonging in the Caretaker Role

Diagramming the interaction patterns allows us to step back from the fray to gain perspective. We may then recognize that our Enabler role, by emphasizing care for others, tends toward the belonging end of the continuum. With conflict posing a threat to our sense of connection, we would thus be less likely to question the Victims’ experience of helplessness and avoidance of risk-taking, or to assert our own need for care and support. This understanding can help us strike a balance between being our own persons (i.e., individuality) and fitting in with others (i.e., belonging).

Summary of Insights Suggested by the Vicious Cycle Diagram

I have often suggested to my clients that they diagram their own unique vicious cycle patterns, rather than relying upon the general models I have shared with them. I have had relatively few takers for this exercise, with most satisfied with the examples I have provided. They usually have conveyed their understanding of the insights that these patterns suggest. These include: the mutual reinforcement of the pattern by both sides, and thus the shared responsibility; yet the need to focus on our own contributions (i.e., “cleaning up our side of the street); and the need to change both our private experiences and our outward expression through word and deed.

Option of Customizing the Diagrams for Specific Cases

While the use of general patterns, like the Victim – Enabler diagram above, is usually enough to guide the exploration, there are advantages to custom-tailoring the diagram to the particular individuals involved. First, the exercise of clarifying our own particular patterns is an act of taking responsibility for ourselves. Second, identifying our own specific beliefs, attitudes, feelings, actions, statements, etc., is helpful in suggesting alternative perspectives. And third, when both parties are on board with the vicious cycle model, the exercise offers an opportunity for an open dialogue. This format allows us to step back away from the fray and to explore the pattern with greater objectivity, and hopefully less blaming and defensiveness.

Open Dialogue

An open discussion about our reciprocal roles in the vicious cycle has the potential for a more complete understanding of the pattern than we might achieve on our own. To the degree that both sides can be open and honest, the mutual sharing of perspectives offers us a glimpse into the one piece of the pattern to which we lack direct access – the private experience of the other. To the degree that we are receptive to feedback, our partners in the vicious cycle can reveal aspects of ourselves that are hidden in our “blind spots.”

The Victims’ Likely Resistance to Breaking the Cycle

Even with these advantages, achieving the collaboration of open dialogue is quite a long shot. Just because we Caretakers are contemplating change does not mean that the Victims are ready to question their perspectives and approaches. Human nature is to double down on our usual approach when challenged – a central feature of vicious cycle behavior. Victims do not give up their roles readily. It is usually necessary to take a stand – to say “no” to the Victims in order to say “yes” to ourselves – before Victims will question their style and consider other options. When we do take a stand, the Victims are likely to consider this as an idle threat and test out whether we will stand our ground. This is particularly likely if we have a history of not following through on our threats (which is quite common for the Enabler role). While open dialogue offers the possibility for greater self-understanding, the dynamics of vicious cycles works against it. Such a discussion is more promising after the cycle has already been broken, with the shared insights helpful for preventing sliding back into it.

Agreement not Required to Break the Cycle

We should keep in mind that mutual agreement is not a necessary condition for breaking the vicious cycle. Here, the saying, “It takes two to tango,” comes into play. We just need to refrain from playing out our Enabler role in the interaction. We can still agree to play out the healthy Caretaker role, with that generally of a more limited scope and tending not to reinforce Victim mentality and behavior. Of course, this shift is not all that simple, as the line between healthy Caretaker and dysfunctional Enabler can be rather blurry. Furthermore, Victims have their ploys (e.g., guilt trips) for pulling us back in. We need to develop our resistance to their tactics, which is an important reason for developing a different outlook on the vicious cycle and our role in it – a topic addressed in the upcoming section, “Changing the Enablers’ Private Experience.”

The Risk of Losing the Relationship

We also need to recognize that breaking the vicious cycle runs the risk of terminating the relationship. When we tender our resignation as an Enabler, there may be others waiting in the wings, ready and willing to apply for that position. Even though we may recognize that such a transfer of enabling will only perpetuate Victims’ unhealthy dependency, there may be very little that we can do to prevent that. We need to recognize that Victims bear the primary responsibility for their choices. While we might have some influence through our advice, ultimately the decisions will be theirs.

Changing our Private Experience and Outward Expression

As addressed earlier in this article and in the earlier Vicious Cycle article, changing our Vicious Cycle role requires both a change in our perspective (i.e., the inner experience inside the diagrammed circle) and in our behavior (i.e., the outward expression inside the diagrammed circle). Suggestions about perspective include letting go of criticism and blame (whether of self or other), recognizing multiple possible legitimate perspectives on the issue at hand, and realizing that everyone involved in the vicious cycle usually loses out in one way or another. Tips on outward expression include realizing that some apparent changes are only variations on a theme (i.e., “same song, second verse), striving toward a middle ground rather than the opposite extreme, and having one’s verbal expressions consistent with one’s personal perspective. With these guidelines being relevant for any of the vicious cycle roles, they can be easily applied to the Enabler role.

Changing The Enabler’s Private Experience

We can generally categorize private experiences as thoughts and feelings. Thoughts can be purely factual, focusing on what is and what is not. These can be checked out. For example, I might be convinced that the Victim in my vicious cycle intends to hold me responsible for his well-being, and that if anything goes wrong, it will be my fault. I could check out my assumption by asking him what he wants from me, what he expects to happen, and who’s responsible if it does not turn out that way. Of course, since his expectations and attributions of blame are private experiences, I cannot be sure that what he says is what he thinks. In this case, I would want to continue monitoring his speech and actions to confirm or refute my belief that he holds me responsible for his well-being. It could be that an apparent conflict over fault and blame is actually a misunderstanding, rather than an actual conflict. In this case, seeking clarification can be enough to resolve the issue.

Unintended Consequences of Inquiry- Good and Bad

It should be noted that the act of seeking clarification may actually have some impact on what we are seeking to understand. In this case, the inquiry may prompt the Victim to question his assignment of blame. He might then take greater responsibility for the outcome in recognizing his role in making the request, which could eventually help him to overcome his Victim role. On the other hand, our questioning might be interpreted as indirect criticism and blame, which are expected to elicit guardedness and defensiveness. While we cannot control the outcome, we can have some influence through our manner of delivery. What we say may not be as important as how we say it. Style points count!

The Enabler’s Opinions, Attitudes, Judgments and Intentions

After having divided private experiences into thoughts and feelings, I am qualifying that distinction by stating that not all thoughts are purely factual beliefs. Some thoughts are not just about what is, but concern what should or should not be. Here, we are entering the realm of opinions, attitudes, and judgments. In these cases, our expectations are influenced by our value system, which we addressed earlier in considering paradoxical dualities (e.g., order vs. freedom, selfish vs. selfless). We might also consider our intentions as a bridge between what is and what should be. These various expectations of the Enabler have already been explored and challenged throughout the paper, such that they need no further review here, except for one reminder: such assumptions are based upon our own personal value systems, and not on laws of nature. Thus, we can expect honest differences of opinion with others, with neither side having the corner on truth.

Respecting Victims’ Differing Perspectives on the Truth

Since no one has the corner on the Truth, we all are fallible experts in our own personal truths. For this reason, we are all entitled to our own attitudes and opinions, whether right, wrong, or just different. While we should honor and respect each other’s truth, we should not necessarily take others’ opinions at face value, as they can be self-serving or otherwise distorted, as is frequently the case in vicious cycle patterns. In addition to evaluating whether their opinions correspond to our own experience, we can always get a second opinion. After all, we all have our own blind spots – remember the beam in our own eyes vs. the splinter in the others’? Still, we can practice acceptance of ours and each others’ personal truths as our own versions of reality. Doing so might allow some inquiry into its helpfulness: the Dr. Phil question of “How’s it working for you?” When we are truly open, the dialogue may help us to identify our implicit beliefs and to challenge them when they do not match up with our daily life experiences. If we want others to conduct a searching inventory on their beliefs, we’d better show our willingness to do the same.

The Enabler’s Feelings

If we were to focus only on our beliefs, attitudes, and judgments related to our Enabler role, this would be little more than a hollow intellectual exercise. While this might suffice for Mr. Spock and his fellow Vulcans in Star Trek, it falls short for us humans. It is our feelings or emotions that motivate our involvement with others — after all, the words “emotion” and “motivate” are both derived from the French verb, movēre, meaning to move.

Our various feelings move or direct us in different directions relative to the persons or causes that engage us. For the Caretaker role, love draws us closer to those who depend upon us. Anger also pulls us toward others, though in a confrontational way. This reaction may be toward those we view as oppressing the Dependents we seek to help, or it may be toward the Dependents themselves, if we feel they are not doing their part to help themselves. Anxiety may lead us to step back in a strategic retreat to develop a plan, particularly if we are adverse to conflict or unsure how to address a problem without upsetting the Victims. Sadness tends to stop us in our tracks, providing an opportunity to grieve over the Dependents’ situation and our limited ability to help. In these various ways, our feelings can guide us toward fulfilling our Caretaker role effectively.

When Feelings Lead Us Astray

While generally helpful in our Caretaker role, our feelings can also lead us astray, as often occurs in the Victim – Enabler cycle. In fact, our emotions might get us lost, just as Siri might lead us the wrong way down a one-way street. For this reason, we need to exercise judgment in trusting them. When our Enabler caring pulls us toward Victims, we need to be careful to give them enough emotional space to do what they can to help themselves. Or we may get stuck in feeling sorry for them and for ourselves, when we need to grieve over the real limitations that confront both them and ourselves. While we may feel like giving up in the face of the Victims’ difficult challenges, often what we need is a temporary strategic retreat to gain perspective and develop a plan. Our frustration and anger may lead us to verbal criticism or blame, when the situation simply calls for setting limits on our availability. In all these cases, it can be helpful to look at how are our attitudes, opinions, beliefs, and judgments are influencing our feelings, with this addressed in yet another of my articles, When Thinking Distorts Feelings.

Changing The Enabler’s Outward Expression

Once we have developed a healthier perspective on our Caretaker roles with our Dependents, there remains the matter of how to channel this understanding into action. Many of the needed changes in expression will be a natural outgrowth from the insights gained from our self-examination. For example, cultivating a more accepting, less judgmental attitude toward our Dependents should reduce any blaming or shaming of them, even when we become frustrated that they are not following our expert advice. Recognition that multiple perspectives can be valid can help in this regard, as well. Our actions guided by such insights can deprive the Victim role of one of its primary driving forces – feelings of inadequacy and shame.

The Importance of Consistency in Thought, Feeling, and Action

With our healthy outlook on our Caretaker role, it is important that our outward expression match up with our private experience. Our words and deeds need to be consistent not just with our “should’s” (i.e., values and expectations), but with our feelings. Caretaking undertaken out of duty and obligation will be less effective than that motivated by compassion. Our motivation counts, perhaps as much or more than the services provided. Taking care of works best along with caring for. Another way of saying this is that thoughts, feeling, and actions work best when in harmony. Such WYSIWYG (what you see is what you get) conveys a sense of authenticity and genuineness. Otherwise, our efforts are likely to come across as patronizing or manipulative.

The Pitfall of “Same Song, Second Verse”

While the above insights are usually necessary for real and lasting change, they are not always enough. We still need ask ourselves what sort of changes in our approach are helpful. One of the main pitfalls is that our new efforts are not so much different from our old ones as they are variations on a theme. For example, we may decide not to do chores for the Victims in our care, but we may end up making excuses for them when Critics attempt to hold them accountable. We continue to reinforce their Victim stance by switching from an Enabler role to a Rescuer one. Both these roles are unhealthy variants of the Dependent style: “Same song, second verse.” Such changes amount to the proverbial rearrangement of the deck chairs on the Titanic: the ship still hits the iceberg and sinks.

The Pitfall of Going from One Extreme to Another

Another unhealthy approach involves going to the opposite extreme. In this case, we may abandon our Enabler role out of frustration, only to adopt a Critic stance. While we may no longer be in the dysfunctional Enabler – Victim vicious cycle, we have just signed up for the equally toxic Critic – Victim cycle. We may exercise various traits within this role, by being critical, punitive, rejecting, or indifferent. As with the Enabler role, this position only reinforces the Victim role by inducing feelings of shame and inadequacy. As I have addressed earlier, pursuit of a role in its extreme tends to be maladaptive, while adopting the middle ground is usually healthier. The solution of going from one extreme approach to another frequently becomes the next problem.

The Pitfall of Alternating between Exaggerated Roles

The solution of shifting from an Enabler to a Critic or Persecutor role is seldom a one-way street. Switching into the unfamiliar and uncomfortable Critic role often induces guilt in ourselves. Victims frequently use various ploys, intentionally or unwittingly, to encourage this feeling. Thus, it is not at all unusual for us to revert back into the Enabler role, at least for long enough to again get frustrated and angry enough to shift back into the Critic role. This back-and-forth presents a double-whammy to Victims, who are likely to feel all the more insecure in their support and are therefore unlikely to test out their capacities for independent functioning. The healthier alternative is to work at integrating the Caretaker role with a positive version of the Critic role, which might be that of Mentor or Coach.

Dealing with Compassion Fatigue

When we have limited Caretaker burnout by cutting back on enabling Victims, we free ourselves up to express caring for them. This compassion can provide solace to the Victims and perhaps even help them to consider how they might better help themselves. This caring can be rather taxing for the Caretaker, resulting in what is termed compassion fatigue. This may result in feeling exhausted, detached, and depressed and in experiencing various physical symptoms, such that it can look much like burnout. While we can consider Caretaker burnout to be a result of excessive doing for or taking care of, compassion fatigue is more a matter of overinvolved being with or caring for. As much as we might protest that we can’t help how we feel, we can look at how we relate to our Dependents and consider other perspectives that don’t get us so consumed in their problems. This does not involve detachment so much as it does a more realistic understanding of what the Dependents are experiencing.

Projecting our Own Feelings unto the Dependent

One perspective which intensifies our emotional involvement with Dependents is our identification with them. In this case, we are imagining how we would feel if we were in their shoes, experiencing what they are going through. This is quite different from listening to them deeply, to hear and understand what their situations means to them and how it affects them. This is a distinction between projecting our own feelings onto them and developing empathy for them. When we project our own feelings onto the Victims, we lose sight of what they are experiencing. With empathy, we both relate to their experiences and gain some perspective on them: we gain the understanding needed to have genuine compassion. This process of really listening helps us to avoid becoming consumed with the Dependents’ problems. Furthermore, this articulated understanding might help them gain a perspective on their problems, helpful for escaping the Victim role.

Underestimating the Dependents’ Resiliency

Another perspective that fosters compassion fatigue is our lack of confidence in the Dependents’ abilities and resilience. By emphasizing the necessity of our Caretaking activities for maintaining their well-being, it reinforces our identities as Caretakers and locks us into this role. We do not so much have compassion for the Dependents as we feel sorry for them or pity them, which is probably more exhausting than actual compassion or empathy. Our message, even if only expressed indirectly and nonverbally, often becomes a self-fulfilling prophecy for the Victim role, encouraging feelings of helplessness and inadequacy.

The Fairness Principle

Yet another factor that intensifies compassion fatigue is the commitment to the principle of fairness. This sense of injustice stokes righteous indignation over the violation of the God-given rights of the Victims (or the laws of nature, to put it in more secular terms). We lose sight of the fact that fairness is a human construct, one which hardly exists in the rest of the animal kingdom. Furthermore, there are certain situations for which the fairness principle does not apply, such as “accidents of birth” and natural disasters. Rather than considering fairness as a preordained right or a natural law, it is better seen as an ideal, a human convention that we strive for. While we can work at “leveling the playing field” of life by mitigating certain inequalities and at easing suffering, we cannot defeat the “slings and arrows of outrageous fortune,” whether for ourselves or for the Victims we seek to help. Gaining a more realistic perspective can be a humbling experience, one which requires grieving to accept fully. By helping meet more realistic expectations, this more limited ideal of fairness can help ease our compassion fatigue and perhaps suggest practical strategies which Caretakers and Dependents alike can use to achieve greater fairness.

Summary

Avoiding Caretaker burnout usually requires changes in both our private experiences and our outward expressions in word and deed. This is particularly true when the Caretaker role has become a central to our personal identity, overshadowing our self-care. We need to challenge our reluctance to care for and take care of ourselves in the same way that we do so for others, including our avoidance of making ourselves vulnerable. We also need to find the proper balance between doing for and being with others. When those in our care have major limitations in their capacity for self-care, they will naturally need more doing for them. For others, those with good self-care skills yet undergoing acute stress and/or having a crisis of confidence, being with them compassionately will often be enough. In contrast, the Enabler role (i.e., a pattern of doing for others what they can and should do for themselves) can be quite harmful to both them and ourselves. Our Enabler role encourages our Dependents to adopt a Victim mentality, thus establishing an Enabler — Victim vicious cycle of relating to one another. When our excessive Caretaking is coupled with our own self-denial , our Enabler role can morph into a Martyr role, a version of the Victim role, which only makes matters worse. We may become frustrated and resentful toward those we trying to help, when the problem is our failure to set limits and our own lack of proper self-care. Our resulting lack of compassion can undermine whatever benefits our Caretaking provides to our Dependents. To counter these negative effects, we need to affirm our self-worth by saying “no” to others so that we can say “yes” to ourselves. Doing so will help us to find a proper balance between being-for-others and being-for-ourselves. We balance practicing the Golden Rule with exercising what I call the Inverse Golden Rule. The latter involves both doing for ourselves what we would do for others, and allowing others to do for us what we do for others. Such outward expressions of our self-worth put our recently developed healthier private perspective into action. In doing so, we are better able to exercise a healthier version of the Caretaker role and to limit Caretaker burnout and compassion fatigue.